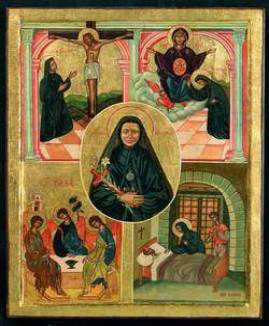

St Maria Bertilla Boscardin

Passages from the book:: RITRATTI DI SANTI

by Antonio Sicari ed. Java

Book

There are words from the Gospel that we

often hear and keep in our hearts but which we find hard to fully understand

and even more impossible to put into practice: “

There are words from the Gospel that we

often hear and keep in our hearts but which we find hard to fully understand

and even more impossible to put into practice: “

“No; anyone who wants to

become great among you must be your servant, and anyone who wants to be first

among you must be your servant…” (Matt. 20, 26-27).

With

discomfort we also read the parables of the guests who choose the first places,

while, according to Jesus, it was wise to prefer the last place, which had the

privilege of the possibility, that He who was the Master of the house, would

see us and call us to sit beside Him, just as a friend treats a friend.

For certain,

the saints obeyed this word. They searched with true humility for the last

place as slaves, in order to resemble the Lord Jesus who “came to serve and not

to be served”; and nevertheless, they almost always appear as though they were

wrapped in an aura of splendour: mighty at times in the events of their lives:

at times even in their sins from which they had to be torn from by force;

mighty for the graces by which they were filled, or the miracles that

accompanied them, or for the works they achieved in carrying out.

Some of them

even succeeded in being great in humility, in littleness, just like Saint

Theresa of Lisieux, even to the point of odium, like Saint Joseph Benedict

Labre. This is the reason why many find it hard to understand and to put into

practice what we are speaking about. What is there be said when even the last

place cannot be chosen? When it is a humiliated, daily condition, in which you

are born and in which you must abide that which ruins the normal growth of the

ego? When “feeling inferior to everyone else” is not a virtue, but a complex

that should be taken care of by the freeing arts of psychoanalysis?

In these cases

we seem to come up against a paradox. Those who are really the ‘last’, in every

sense, are not facilitated for sanctity, in fact they are unable to think or

believe it possible for them.

And since,

even thought it does not seem so, they are many who think that they are ill-treated

by life, and therefore the consequences are that many feel excluded from

sanctity rather than called to it.

The Church

preaches to it’s children about the “universal vocation of sanctity” but the

hearts of many object to this; there are conditions and conditionings, which

have their beginnings from infancy and make even a normal life impossible, not

to speak of sanctity.

On an evening

in October, 1919, Sister Maria Bertilla Boscardin, a nurse in the hospital in

Treviso, took part in the enclosure of the Carmelite Discalced of the city for

the celebrations requested by the Fathers (“tritium solemn honours” was written

on the door of the consecrated building) to celebrate a newly Beatified of

their order: Blessed Ann di San Bartolomeo, who had been secretary to the great

Theresa d’Avila.

The Church was

full of lights, ornaments and festive rites: “ let us become saints too”, whispered Sister Bertilla to her

companions, “but saints in heaven and not

on altars”.

This way she

tried to coincide with two requisites, which for her were difficult to

reconcile: her profound desire for sanctity and the consciousness of her

insignificance that could not bring her to imagine herself worthy of such

honour.

Thirty years

later and she herself will be risen to the “Glory” of Bernini.

Where saints

are concerned, the Church is not deceived by appearances and recognise them in

the figures of both Popes (Pope Pious X lived and was beatified in these years)

and in that of a humble servant nun who was a nurse.

Maria Bertilla

received this name from an Abbess who was of antique and noble origin, during

the period of the Frank, on her entering the convent. But, even this solemn

name seemed humble and ungraceful on Maria.

She had been

christened Ann Francis; in her family and town she was known as Annette.

She was born

in the small

Her mother was

a kind woman while her father was harsh and quarrelsome. His touchy character

and jealousy worsened terribly when he was drunk; he became suspicious of his

wife and covered her with rebukes, shouting and beatings.

The neighbours

heard the shouting and shook their heads; they could do nothing more than take

the child into their homes when she fled from her home terrified, she would sit

in a corner, covering her eyes with her hands..

Sometimes

Annette threw herself on her mother’s lap to protect her more than to protect

herself; other times they succeeded in escaping to the loft; once they fled on foot

towards

So the child

grew clutching to her mother, afraid of her father, used to the hard work both

in the home and fields shy, awkward, and her scholastic results were poor.

She attended

the three school classes in the village and had to repeat the first class,

which was a very strange thing even in those days.

At school and

in the village she acquired the nickname of “the goose”, and all her life this

nickname will remain with her both at home and in the convent.

If, at this

point, we imagine a dialogue, in heaven, between God and the Enemy (similar to

the tale, in which the Bible tells of Job), we would hear the voce of our “poor” faith and the doubts of which we

speak, and say to the Lord of the Universe: “Here

is a really humiliated creature, try and make a Saint of her, if you can”.

And God

accepts the challenge.

Not, however,

by taking her from that condition of Cinderella and making her hidden beauty

shine, but by simply using, as it is in His plan, those lacerations that

pedagogists and psychologists know how to foresee and describe so well.

Shy, awkward,

and apparently of no value, Annette will remain all her life, always at the

last place. It is there, at the end of the table, that Jesus looks on her with

love, as He had promised in His parable. And from there he will call her to his

Heart.

If her father

was exacerbating, and the house cold and sad, she learns from her mother to

take refuge in the small church in the village as though it were a home. She

went there every morning, very early, carrying her clogs in order not to ruin

them. There she understood what a real family was like and she felt in peace

with all, even with that father who no one understood but condemned. After all,

daddy had not a cruel heart, but it had hardened on account of his drinking

wine and the difficulties he had and at times he noticed the child who tried to

pray even at home.

When ‘he’,

will have to give evidence at the canonical trials for the beatification of his

daughter, he confesses that, sometimes, seeing the small child on her kneels in

a corner “with her hands in courtesy” (an antique way of saying “joined

hands”), a lump would come to his throat and he felt as if he was going to

choke, and he felt an urge to recite some Our Fathers.

At school no

one took any notice of her considering her to be noticeably below average in intelligence;

sometimes her homework was not corrected and her schoolmates, with the cruelty

of their age, never forget to make her aware of the fact. “I really don’t mind”,

she would answer humbly, and she truly did not feel anger or rebellion.

Only once will

the teacher and her schoolmates remain uncomfortable before her, as though in

the presence of an unknown world. During Holy Week the teacher tells the class

of the passion of Jesus and Annette, burst into tears heartbroken: “I am crying for the sufferings of the Lord,

and because men are so cruel”, the child explained in her dialect.

It is for

certain that the parish priest, having taken a more authentic and profound look

at this child, going against the opinions and to the marvel of all, he will admit

her to Holy Communion at eight and a half years old, when the authorised age in

those years was eleven.

It was the

year 1897; the year in which Theresa of Lisieux died, the saint who would

remind the Church and the enter world of the tenderness with which Gods looks

on what seems to the world to be small and weak.

At twelve

years old, the parish priest infringing the rules once again, accepts her to

join the association of the “Children of Mary”, in which the girls could join

only on having reached the age of twelve.

That saintly

priest looked at the child’s soul, he loved her and she did not seem so

ignorant to him. He gave her a catechism as a gift and he seemed to have an

intuition that she would always keep it with her and study it every day: they

found it in the pocket of her habit, when she died, at thirty-four years old.

The parish

priest was also taken by surprise when the fifteen year old girl tells him that

she wishes to consecrate her life to God, in any order, it was not important,

he could choose,

“But you are not able to do anything! The nuns would not

know what to do with you!”

“That is true, master” the girl candidly answered (in her dialect).

So he explained that it would be better if she remained at home and

gave a hand with the work in the fields.

But when the

priest was praying before the Blessed Sacrament and the things he had said did

not seem to be so obvious.

When he met

her again he asked her:

“Are you still decided on entering a convent? Tell me something: do you

know how to peel potatoes at least?”

“Oh yes, Father, I am able to do that at least”.

“Alright, you need to know nothing else”.

His rough tone was the equivalent to the gentleness of Saint Theresa of

Lisieux, who in those same years had made this observation:

“There are too many people who go before God with the pretence of being

useful to Him”.

It seems that the same conservation, between the parish priest and the

girl, was the same as the one that had been heard in

On the other

hand, the three, Bernradette, Theresa and Bertilla, really seem to be spiritual

sisters.

So she entered

the convent, convinced that they were doing her a great honour in accepting

her, an unmerited favour, and the last place for her would always be the right

one, the right one for her.

She was happy

and grateful for everything: “I will

remember that I am here thanks to a special grace, she writes her note-book,

and everything that I shall receive I

will receive it as something I am not be worthy of”.

At the

beginning her father was annoyed at the thought of having to give a few hundred

lire that were necessary for a dowry, miserable though it be, but he gave in

saying: “It must be her destiny to go

into a convent. Yes, yes, I will give her the money and let her follow he

destiny”.

Thus, twice,

this father who had not succeeded in being a good father, knows how to

pronounce a word that was full of “objective faith”: he perceived a destiny,

which belonged to his daughter and to which he gives in. Having been said by

him, it was a sullen but true acknowledgement of God the Fathers’ law and

rights.

He himself

will accompany her to the convent, pulling the cart with his daughter’s poor

dowry: an earthly picture which most surely moved our Heavenly Father, and made

this man, uncouth and of poor faith, worthy of the grace of a holy death, at an

old age, surrounded by reverence and affection, thanks to his daughter who had

become a saint.

During her

novice-ship, that which Annette, now known as Sister Bertilla, would have had

to learn by mystical practice and virtue, she already knew “naturally”.

She will have

to learn the fundamentals of all spiritual lives and all the mystics; that is:

God is All and the nullity of his creatures, on which Frances d’Assisi,

Catherine of Siena, John of the Cross and thousands of other saints, had

lengthily mediated, and will not argue or find tiring.

She will have to

practice to learn to know God and to learn to know herself (according to the

Saint Agustine’s aphorism: “Noverin Te, Domine, noverim me”, and she, unaware,

would explain to a companion that this was so obvious: “When we are humiliated, we should not loose time in pondering on the

fact, but say to the Lord: that I may know Thee, that I may know myself”.

She was really convinced of her “nullity” and that the others,

educated, capable, were all better than her and that they all had the right to

her attention and services.

She would go

to the Teacher and ask with disarming genuineness:

“I am not able to do anything. I am a poor goose. Will you teach me

what I must do? I want to become a saint”.

To us, who are careful and will fight to the end in order to maintain

the prestige we have earned, and make it a question of dignity, this could

cause us to be annoyed in seeing a creature reduced to such a degree of

humility (or perhaps of humiliation). But we must not allow ourselves to be

deceived.

With all our dignity,

we are afraid or ashamed to say that we want to become saints. She considered

it a right and a necessity.

It is as if

our pretentious dignity often guards a fragile and uncertain ‘ego’; while

Bertilla’s humility and even her auto-humiliation guarded an ‘ego’ that was

consistent and as pure as a diamond

It was her

desire for sanctity, and the certainty that it was possible even for her to

become a saint, through the grace of God, that protected her from retiring into

herself, from nervous breakdowns or existential crisis’s. It was this desire

and certainty that made her “living at the last place” evangelic.

For the same

reason, she experienced the profound beauty and truth of the words like,

“obedience”, “poverty”, “humility”, “silence”, “kindness”. It was congenial to

choose the undesirable places, the hardest work, the generous duties and never

complaining. “ I’ll do it, she so

often said, for tasks that no one else wanted to do, “I’ll do it”. It’s my duty”. Even when they did her wrong or they neglected

her; she never seethed in the offence.

At the end of

her first year as a novice she was sent to the hospital in

It was a

hospital with a lot of problems, in phases of continuos refurbishing, with

inadequate divisions and unprepared staff, a theatre of Trade Union and

political conflicts, of virulent clashes between freemasonry, socialists and

clergy, which often boomeranged back on the nuns.

In 1907, when

Bertilla, nineteen years of age, entered the hospital, three nuns were sent

away, out of spite more than for valid reasons. The newspaper Voce del Popolo, (a diocesan weekly) published

a significant paragraph: “They sent them

away. They were three angels of charity (…)who assisted the ill with maximum

care and self-denial (and…). They drove them away as if you would, thieves,

giving them eight days to find another roof and another master. The Hebrew Lord

Mayor and the freemasonry Borough Council clerks, just to please the socialist

scoundrels…they sent them away”.

This was the environment and the atmosphere.

Here she found waiting for her a Mother Superior who was efficient and

brisk who gave her a quick look, she esteemed her immediately and sent her to

the nun’s kitchen, to be a dishwasher, without the possibility of having

contact with doctors or patients. Here she will remain for a year, without

interruption, among stoves, pots and pans and the sink.

On the other hand, during her novice-ship, she wrote this prayer in her

note book of spiritual notes: “My Jesus,

I implore you through your Holy Wounds that I may die a thousand times rather than

permit that I do a single action in order to be noticed! “

Therefore she did not rebel when they confined her to this place where

there were no possibilities of being either admired or in doing anything that

was to merit the attention of others. Certainly, her heart and desire was to

look and take care of the ill, but she had been told to remain in the kitchen

and take care of the cutlery and she learned to wash plates, while praying. “My Lord, wash my soul and prepare it for

tomorrows Eucharist ”.

If she had done this complaining both with her lips and heart, then she

would had been a slave; but with that prayer, in her ‘last place’, she looked

at God and this was enough for her to feel invited to God’s altar.

After a year she was recalled to

When she became a nun having taken her vows, they sent her back again

to the hospital in

Naturally they sent her once again to the kitchen. Ten days later one

of the responsible of a very difficult and delicate division died. At first the

mother Superior dispelled the temptation of thinking of giving Sister Bertilla

this responsibility; but there was no one else. She even prayed to God to forgive

the imprudence committed, then she however entrusted the division to Sister

Bertilla.

Thus, at twenty years of age, Bertilla began her mission as a nurse.

The division was that of contagiously ill children; almost all these children

had diphtheria, they had to undergo tracheotomy or intubating, in need of

continuous assistance; a distraction could mean a child’s life.

Above all life was a continuous regime of urgency, without fixed

timetables, without any outside contacts, not even for daily mass.

We must remember that we are in an epoch in which children often arrive

from faraway towns in the middle of freezing cold nights, in serious conditions

for the septicaemia in course, in wobbling carts, cyanotic from the progressive

asphyxia, in need of the intelligent, immediate assistance of all.

It was on one hand the contact with the children, on the other the

participating in these sufferings so tragic and innocent that seem to free

Sister Bertilla of her awkwardness, all her shyness and make her “sweet”,

tranquil, serene, shrewd”, as the doctors said.

It is opportune to read the testimonies of the doctors who had her as

an assistant. Here is one: “Children are

admitted to the ward with diphtheria; they have been taken from their families

and they find themselves in such a state of agitation, of depression, so much

so that it is not easy to calm them, for two or three days they are like little

beasts, beating, boxing, rolling under the bed, refusing food. Now Sister

Bertilla succeeded in rapidly becoming a mother to them all; after two or three

hours the child, who was desperate, clung to her, calmly, as to his mother and

followed her wherever she went. The ward, under her action, presented a moving

spectacle: groups of children clinging unto her. The ward was really exemplar”.

It may only seem to be an affable picture, but then the doctors go on

describing what happened with the parents when the death of their child had to

be announced. She was the only one who was able to find the

appropriate words for their despair. The doctors themselves, moreover (the

young doctors especially who were terrorised in having to practice their first

tracheotomy), will always find her by their sides, without a sign of

nervousness or tiredness, in the most critical and agitated moments.

It even happened that when it was time to leave the hospital, the

children would cry because they had to leave her and the doctors smilingly tell

of the episode of the little girl who said she could not go away because she

had “so much affection for the nun”.

“Sister Bertilla always gave

me the impression that there was someone beside her who guided and helped her;

because a person who rises, in their mission of charity, above others, who also

live by the same laws, behave with the same tension, while not having (looking

at her materially) any quality or intelligence or culture that would make her

superior to others, she really gave the impression that she acted…as if she was

following an angel that conducted her. It is not possible for a doctor to think

of a person like Sister Bertilla, who

passes one, two, three, fifteen nights without sleep, and she presents herself

always in the same manner, neglecting herself, without signs of tiredness or

the illness that undermined her, I repeat, something inside and outside that

sublimated her..Not only, but the fact that she transited such an influence on

other, such a persuasion that is not found in other people.”.

To note that the doctor who describes her like this is a free- thinker,

a freemasonry who will convert, as we will tell further on, when he sees her

dying “full of joy”.

Sister Bertilla will spend two years with the ‘contagious’ patients,

than she will spend time in all the divisions, leaving behind her, in her fifteen

years of hospital life, the same dear and holy memory.

Another sister will tell of how at times, when the nuns were in the

refectory, and some new patients arrived. If the responsible said: “There is a patient for Sister Bertilla”,

“everyone knew that it was a poor miserable person, miserable and full of

parasites, if not tuberculosis”. She had given the others the habit of

turning to her when particularly unpleasant situations were presented, from

which not only the nurses but the hospital attendants also fled.

When the Mother Superior told her to be cautious, she answered:

“Mother Superior, I feel as

if I am serving God”, and she never avoided excessive work or defended

herself even when ill-treated by the more nervous patients. She seemed to have

no pride, but only the desire to love and serve.

In 1915 the Great War broke out, when the Piave became the most

advanced line, danger was immediate and constant: “In these times of war and terror, Sister Bertilla wrote in her

faithful note-book, “I pronounce my

“Ecce, venio!”. Here I am, Lord, to do according to your will, under whatever

aspect it presents itself, let it be life, death or terror”.

It might seem to be a nun’s pious prayer. It was a silent and heroic

choice, each time that the bombs hit the city and everyone ran to the shelters,

to remain beside the beds of the patients who could not be moved; praying and

giving glasses of

She would become pale, terrorised even more than the others would, but

she remained.

“Are you not afraid, Sister

Bertilla?” the Mother Superior would ask her.

“Do not worry, Mother” she answered, “God gives me such much strength that I do

not even feel it”.

And so they sent her to the Lazzeretto (a dependency of the hospital),

situated near a railway joint, that was mostly the object of air attacks, to

substitute a nun who could not stand the fear: “Do not think about me, Mother”, she would say to the responsible

who felt guilty about asking her to sacrifice herself, “it is enough for me to know that I can be useful”.

In 1917, after the evasion of Fruili, the hospital had to be evacuated

and the patients were divided into three groups. Sister Bertilla left with two

hundred patients for Brianza and they put the patients who had typhus in her

care. Then in 1918 they sent her to the

To tell how she lived such a Via

Crucis, would be repetitive; because the sanctity of this humble woman

consists in the continuity, never interrupting of words, gestures, attitudes,

decisions, that always went in the same direction, with that daily fidelity in

all trials, that is the greatest miracle to be seen.

We are not talking only of a post

mortem letter, or of a successive revocation, when we tend to see

everything beautiful and good.

When a chaplain lieutenant, in that same year, returned home fully

recovered, he felt it his duty to write a letter to the general Mother

Superior, to thank her “for the good work

that her Daughters were doing in that house of suffering…Among them all, he

writes, Sister Bertilla distinguishes

herself. She is occupied with the soldiers who are on the top floor of the

hotel, which has been turned into a hospital; she is all consuming in care and

charity, as a mother would for her child, a sister for a brother. The

necessities of the poor souls, certainly compassionate in their incurable

decease, where many, and the organisation of the hospital made it very

difficult to distribute what was necessary. Sister Bertilla, in order to find a

balsam for a patient would have gone through fire, she could not rest and the

number of times she went up and down those long stairs (100 steps) to the

kitchen to fetch something or another…”.

Years later in order to be more precise, he will tell of an episode

that makes us understand the charity that marvelled him.

“The Spanish influenza had

hit our hospital; the victims of this epidemic were dozens, many of whom died. The

fever, of which almost all of us were affected, rose to frightening

proportions. We slept with the windows open; these were the sanatorium orders,

and in order to moderate the coldness of the night the use of hot water bottles

was allowed. It happened on an evening in October that the boiler broke-down,

which meant that this small comfort was not possible. I cannot explain the

uproar that went on during that hour. The vice-director tried to calm the

up-roar, trying his best to make the soldiers understand that the desired hot

water was not available for everyone: and furthermore the kitchen attendants

were entitled to their rest. What a surprise for all, when late during the

night, they saw a little nun who was going around the ward, from bed to bed, giving

every patient the desired hot water bottle. She had gone to trouble of lighting

a fire in the yard and heating the water in small pots.. The morning after

everyone was talking about that nun who had come back on duty without having

rested or slept..”.

As a reward she found a meticulous superior, who was only worried that

Bertilla was too attached to her soldiers. Such care she took, seemed

excessive, certain preoccupations too involving; and her patients became too

fond of her, in her opinion, exaggerating. So she relieved her of her

responsibility in the sanatorium and sent her to the laundry, where her job was

to secrete piles of infected bed linen. Furthermore, as the superior considered

that work of little importance, every now and again she did not forget to

observe (with the cruelty of which only the mediocre are capable of, even more

than the wicked) that Bertilla “did not even earn the bread she ate”. It was

Sister Bertillas time of “passion”.

The Mother Superior went so far that Bertilla was sent back to the

motherhouse: “Here I am, Mother, she said on her arrival, “her I am a useless nun that can be of no

good to the community”.

Jesus had used the incomprehension of creatures in order to answer the

prayer that she often prayed to Him: “To

always be with you, in Heaven, I want to share all the bitterness of this

valley of tears: I wish to love you so much, by sacrifice, by the cross,

suffering”.

Who wants to escape at all costs, from sufferance, will never be able

to understand the miracle that happens when the desire to participate in

Christ’s Cross takes hold of a heart. It happens as though Jesus’ passion is

renewed for us, to save all the souls on earth. The

What she writes, during those months, in her notebook are saturated

with her love for the Blessed Virgin, it was as if She was once again with the

child and her mother under the portico of the same Sanctuary.

“Oh my dear Madonna, I do

not ask for visions, or revelations, or pleasures, or kindness, not even

spiritual ones. In this world I do not wish for anything more than that which

you wished for when you were here on earth; to believe with all my heart and

soul, without seeing, or pleasure, to suffer with joy, without consolation. To

work hard for you, until I die”.

After five months she was able to return to

Always the same goodness, the same humility, the same peace and the

same inexhaustible impulse to give, notwithstanding a visceral tumour had been

killing her for some time. She had undergone surgery at twenty years of age,

but the tumour had not stopped spreading. Then again she neglected herself,

because of a misunderstood and invincible sense of modesty

She became more and more spiritually detached from herself: “I have nothing that is my own, only my free

will, and I, with the grace of God, am ready and resolute, cost what it may, to

never do as I wish, and I do this out of pure love of Jesus, as if neither hell

or Heaven exists, or even the comfort of a pure conscience”.

Without ever suspecting, she reached summits, which only the greatest

mystics had reached.

On

The news spread through the hospital that Sister Bertilla was dying and

immediately it was a rush of the head physcian, doctors and nurses, to her

room.

“You would think she was a

saint!” said one of those sisters who had always considered her a “good for

nothing”.

Some, seeing her suffering so meekly, in tears tried to console her. “You must not cry. If we want to see Jesus,

we have to die. I am happy”.

However, she spoke in her dialect, as she had always done. “You must tell the sisters, she said to

the Mother superior, that they must work

for God because everything else is wothless, everything else is worthless”.

Zuccardi Merli, the doctor who was a free- thinker and freemasonry, of

whom we have spoken of, watched Sister Bertilla as she was dying and he felt

something change in his heart: “I can

assure, that the dawn of my spiritual change was given through the vision of

Sister Bertilla when she was on the verge of death,” he witnesses. “In fact, for her, whose hand I kissed

before she passed away, dying was so visible for everyone, a joy. She died a

death like no one else I had seen dying, like someone who is already in an

improved state of life. Oppressed by an atrociously painful ailment, bloodless,

certain she would die, in that state in which the patient usually clutches to

the doctor and asks. ‘Save me’, to hear her pronounce with a smile that I

cannot describe: “Be happy, my sisters, I am going to my God”, this was the

thing that suggested an auto criticism on my part and that now I see as being

sister Bertillas first miracle. In fact I said to myself: “This creature is as

though she was far from us, even if still alive. There is a part of her that is

material, that which remains with us, that gives thanks, that comforts those

around her; but there is a spiritual part far from us, above us, which is more

evident and domineering: the spiritual part that is already rejoicing in that

happiness that had been the yearning of her life…”.

In these words, apparently difficult and complicated, you can hear the

rationalist who has been put before the evidence of the supernatural; he who

had always denied the existence of a soul, is almost constricted to seeing it

while God retakes it and startles it with joy, and the body abandons.

Thus, this humble little nun, who everyone had considered “a poor

goose”, takes with her, in her faith, that intellectual who was so proud of his

science and his freethinking. She who dying had in the pocket of her habit a

worn-out catechism and who usually said:

“I am ignorant, but I

believe in everything that the Church believes in”.

To a nun who was questioning her on her “spiritual life”, she answered:

I do not know what it is to ‘savour the

Lord’. I am quite content by being good at washing plates and offering God my

work”. I know nothing about spiritual life. Mine is the “the way of the carts”.

She always felt the country girl who was used to country roads, roads

that lead to work, roads on which one travels without airs, pretences of

elegance or distractions.

This country girl knew how to write, in her Italian full of grammatical

errors, words full of nobleness and purity.

“God and I alone, internal

external recollection, continuous prayer, this is the air I breath;

never-ending work, diligent, but with calmness and order. I am God’s creature,

God created me and he protects me, reason wanted that I am entirely His. I seek

happiness, but true happiness I find only in God. I must do God’s will without

asking for anything in return, with no other desires, with cheerfulness and

laughter. I implore God that he may help me to win my ego, to understand what

is right and what is wrong, that He may help me to do at all costs His holy

will, without asking for anything more…..”.

When she was beatified in 1952, Pope Pious X11 said: “She is not a dismaying model …In her

humility she defined her path as ‘the way of the carts’, the most common, that of the Catechism”.