Translator Antoinette

Passages from the book RITRATTI DI SANTI by Antonio Sicari ed. Java Book

St. Frances Xavier Cabrini

The Jubilee year 2000 is not only a passage of time between the second

and the third millennium, but it is the year of celebration of the 150th

anniversary of the birth of Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini which took place in

Sant’Angelo in the province of Lodi and the 50th anniversary of her

proclamation as the Patron saint of emigrants (17th September, 1950)

by Pope Pious X11, by whom she had been canonised in 1946.

The Jubilee year 2000 is not only a passage of time between the second

and the third millennium, but it is the year of celebration of the 150th

anniversary of the birth of Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini which took place in

Sant’Angelo in the province of Lodi and the 50th anniversary of her

proclamation as the Patron saint of emigrants (17th September, 1950)

by Pope Pious X11, by whom she had been canonised in 1946.

In a biography

of Mother Cabrini, known as “the Saint of the Italians in America”, these are

the precise words that are written: “In the America of the19th century,

mothers and grandmothers, who wanted to scare their lively and restless child,

instead of naming the ‘ghost’ they would cry: ‘Here comes an Italian!’ and the

child would immediately run and hide on their laps.

It might seem

just to be a colourful note, but these are among the saddest things that were

written on the tragic incidents of our emigrants, between the end of the last

century and the beginning of the 20th century.

It is the

period during which signs are exposed outside of bars in American cities to

notify that entrance was forbidden <<to niggers and Italians>>,

being that Italians were considered as <white niggers>>.

Between 1876

and 1914, shortly before the first world war, about fourteen million Italians,

according to our statistics; <eighteen million!> is the number maintained

by the countries that were invaded by the throngs of our poor co-nationals. The

entire population of Italy did not reach thirty million at the time!

In history

books we read of the great migrations of nations and of the times during which

entire nations were reduced to slavery, but we omit the fact that the history

of our emigrants was in fact the very same.

Italo Balbo

wrote that all those co-nationals – swallowed up in coal mines, in the digging

for railroads, in oil wells, in iron and steel industries, in the textile

industries, in shipyards, in cotton and tobacco plantations – were <non

one’s Italy>, an anonymous population of <white slaves>, <human

material traded in millions>.

It is

calculated that the number of Italians working in mines, at a certain point,

exceeded that of the total amount of emigrants put together. They arrived in

hundreds of thousands a year, harassed from the time the left up to their

arrival by sinister commission agents who took advantage of their ignorance and

need, deprived of protection, agreeable to anything they proposed; thus

literally becoming human material on which – necessary debris of no value – the

American economical potency was built.

They lived in

incredible conditions of decay, crowded in human beehives (up to eight hundred

people packed into small building of five floors), in beastly physical and

often moral conditions. With their style of life they seemed to give credit to

the idea of an Italian as a half-savage, violent and always ready to come to

hands.

They lived

without schools, hospitals, churches, closed in their ‘little Italy’s’,

districts, which proliferated in the suburbs of big cities. They were almost

never even ‘little Italys’’ because the various localisms were the cause of

their separating and putting the various regional groups one against the other.

The children lived on the streets. A future as shoe-shiners or newspaper

sellers awaited them.

The

impossibility of communication (almost all of them were illiterate and they

expressed themselves in dialect) making all tentative of solidarity vain.

Those who

succeeded in making a fortune (and many started vegetable shops or organising Mafia

clans) were careful not to mix with their own despicable co-nationals, trying

rather to forget their communal origin.

One day in

1879 a deputy dared to read a letter from a Venetian colonist before the

Italian Parliament: <We are here like

animals. We live and die without priests, teachers, doctors>. The

Italian politics however, took no heed. The looked at the problem of emigration

from a point of view of public order, with some provision of police, but with

non intelligent perception of any form of economic or social tutelage.

Some years

later – when Sister Cabrini herself will have done, for the love of Christ,

that which the entire government had never succeeded in doing – the

politicians, looking back on their legislative pseudo-precautions will say: <We went wrong in everything>.

Not even the Catholic Church in America could do anything. In the whole city of New York there were only twenty priests who understood a little Italian. To make things worse, our emigrants found the costumes, strange for them, that compelled attending the Church also an obligation, before entering the church, of contributing economically to the up-keep of the parish activities. They were already poor and a similar costume seemed unjust to them (they called those aims ‘the customs duty’). Not to say that the sole Italian organisations present were the <Giordano Bruno> circles, whose only worries were to spread and maintain a fervid anti-clericalism.

So they

stopped attending the Church and many of those last shreds of spiritual and

moral dignity, were lost.

|

|

In Italy the

problem was perceived by Pope Leo X111 (who presented and faced the problem in

the famous encyclical Rerum novarum) and

by the Bishop of Piacenza,

Scabrini who

had founded a congregation to look after the emigrants.

Frances

Cabrini was a Lodigian who had desired to be a missionary since she was a young

child, when her father read to the children, during the long evenings, the Annuals of the Propagation of the Faith, she

would sit day dreaming. She dreamt in those days of mysterious China. She went

as far as to stop eating cakes when she was convinced that in China they did

not have cakes, so she had to prepare herself.

She had become, after many hardships, the founder of a small religious congregation aimed at missionary life, a strange project for a female institute, and she felt ready to make her old girlhood dream come true.

She met Bishop

Scalbrini who tried to make her change her mind describing the miserable

conditions of the emigrants in America.

Frances was

confused and so she decided to leave the decision to Pope Leo XIII, who

listened to her lengthily, then decisively told her: <Not in the Far East, Cabrini, but to the West”> . It was as

though the same word of God was indicating His will to her.

She was

thirty-nine years old, she had lung problems and the doctors had given the

prognoses that she had not longer than two years of life to live.

She left with

seven companions; the ship on which she made her first trip, carried 900

emigrants in 3rd class.

She arrived in

New York at the end of March, 1889, she had been informed that the Arch Bishop

Corrigan and an American noblewoman, the wife of an Italian Earl who had become

the director of the Metropolitan Museum

of Art; would be there to meet her, but the two had had quarrelled over of

points of view and disagreements of programming, and they had written to Italy

advising that the departure be suspended.

The result

being that there was nobody to meet the nuns. It was pouring rain when they

went ashore, as God granted, they arrived at the poor house of the Scalabrini

fathers, soaking wet and tired, but they had no means of giving them

hospitality. They ended up in a lurid lodging near the Chinese quarters, where

the beds were so dirty that they hadn’t even the courage to lie on them: they

sat on the floor shivering from the cold resting their shoulders against the

wall.

The archbishop

received them, the day after, and briskly advised them to return to where they

had come from. <Never, your

Excellency, I am here under order from the Holy See, and her I must remain>

- she answered.

In the end,

and with the help of the countess, she succeeded in opening a small school for a

few orphans, that she called “The House of the Holy Angels”.

Whereas, the

countess, in obedience to the archbishop, organised a big school for the

Italian children. It was a sui generis. The

children arrived in enormous numbers; there was no other place to put them up

but in the poor Scalabriniani Church, and there, between one service and

another, in spaces made in the choir, in the sacristy, in corners of the church

curtained off, her the classes were established. The benches were used as desks, the kneeling benches as the

teacher’s desk.

The nuns, who

were teaching, often began with the washing and combing of hair of that crowd

of dirty and ruffled boys. In the afternoon they had catechism, followed by

playing the courtyard, a hidden and unhappy place sunk between high and dark

buildings.

In her free

time, and until late in the evening, Frances Canrini, would plod through the

muddy lanes of the Italian quarter, in search of those parents who otherwise

she would have never known.

In a paragraph

of the New York Sun, dated the 30th

June, 1889 we read: <During the last

few weeks, some women, dressed as Sisters of Charity, are going through the

Italian quarters of the Bend and Little Italy, climbing narrow and long

stairways, going down into dirty basements and in certain dens where not even

the New York police would dare to enter alone>.

Notwithstanding the countess’s help, the principal problem of money remained. Therefore, the nuns began to travel through the city looking for help, refusing, on principal, all discrimination.

In an

environment where division reigned (between the same Italians who were

separated into groups of families and localisms), where the Catholic Irish

considered the Italians as neo-pagans and where the<natives> met to

organise <the ethnical protection>, those nuns moved with dignity and the

graciousness of love.

They were accepted beyond their utmost hopes: shopkeepers of every race and religion came to the door of their shops to call them and pack them with merchandise; business-men decided to give them a cheque; the owners of markets gave orders that no one was to stop or ill-treat those courageous nuns; a Jewish German carpenter gifted them with furniture that was to furnish schools and orphanages; the Irish nationalists, demanded that the police stopped the traffic when the nuns were passing with their household effects, because “they represented the Pope”; passengers on trams stealthy put a few dollars in their hands.

Meanwhile, the

“House of the Holy Angels” had expanded and was attended by coloured, Chinese

and mulatto’s children.

On the 17th

of July, 1889, an organised procession of three hundred and fifty boys and

girls, paraded through the streets of Little

Italy; the girls wearing their veils and carrying their rosary beads, the

boys wearing their armbands of the association; in groups of thirty, carrying

their St. Louis, Saint Agnes and St. Anthony banners.

Who still

remembered certain processions that were once held in their parishes, when the

associations were flourishing, can have an idea of the tenderness of a similar

picture; but it is impossible for us to imagine the expressions of the Irish

and the protestants at the sight of these boys and girls who paraded in silence

and dignity, those same children that they used to consider lurid and

disorderly thieves.

The first

battle had been won, but they were only at the start.

Frances

returned to Italy in the same month, to take care of the novices of her

Congregation. While in Rome, she heard the news that the Jesuits in America

were selling a huge estate in West Park,

on the banks of the river Hudson, 150 miles from New York.

She returned

to America with seven other nuns and succeeded in putting together the five

hundred thousand dollars that were necessary for the deposit. God would think

about the remaining ten thousand. And so she founded the house for the

formation of the Institute, a college, and even a hospice for girls afflicted

by typhus, the decease that was massacring the poor people.

The question comes

naturally: “But where does she get the

money?”. There are thousands of answers, but one in particular is told that

if a benefactor had decided to sign a yearly donation cheque of three hundred

dollars, Frances was able to stop his hand at the last zero, with a smile, and

then – as she was used to with her pupils – she would guide the hand to trace

another zero. Wasn’t this the way to teach charity as you would to read and

write?

There is an

episode that is right to anticipate, because it gives the idea of the aptness

of her style and her faith.

In New

Orleans, in 1892, Frances meets an very rich adventurous Sicilian, who had made

his fortune in ships, beer factories, insurance companies, building societies,

and who was also the owner of about sixteen hundred thousand hectors of cotton

and lemon cultivation’s.

We summarise

the following from a report of the times, taken from a biography by G.

Dell’Ongaro:

“Your visit is an honour for me, Mother Cabrini, all of America are speaking about you. How can I help you?”.

“In nothing. I would like to be of help to you”.

“I need nothing. I asked for nothing from no one, I desire

only to be left in peace and carry on with my business…”.

“I know nothing about business or affairs. But your

happiness interests me. I have been told that you have been married for a long

time. But you have no children. It is sad”.

“Unfortunately it is true, I like children, but…”.

“That’s a pity. A real pity. With all these beautiful things

you have, and not even a son to leave them to. Have you ever asked yourself,

the reason for such a fortune? There must be a reason. I am certain that God

has planned a beautiful project for your life. You do not know the joy that

children can be”.

At this point the man revealed to have thought at times, of adoption, but had always renounced from fear of his wife’s reaction, and ends by saying.

“Let me think about it, let me speak to my wife, and if Maria agrees, then I will call you and you can bring us the child”.

“The child? Who spoke of only one child? Why only one?”.

“How many do you want to give me, Mother?”.

“What do you think about sixty-five, to begin with?

This

businessman will end up financing an entire orphanage. When, some years later,

this building becomes too small, he donated another sixty five thousand

dollars, an enormous amount of money in those days.

Having founded

the West Park house, Frances Cabrini

returns once again to Italy, where she continued to direct her missionary

congregation, which was growing rapidly. She remained to Italy for a few months

and then returned to America with twenty-eight nuns, determined to accept a new

institution in Nicaragua. So she opened a college in Granada that, only four

years later will be demolished during one of the many Central American revolutions.

From here she

moved to south of the United States where she will have an even worse impact. A

large number of Italians mainly from Sicily, emigrated to Virginia, Carolina

and Louisiana, where they found people who were inclined to racial hatred.

Slavery had been officially abolished only thirty years before and the

Americans were not certainly pleasant to those <black-men with pale

skin>, which was their definition of our emigrants.

The Sicilians

however, were not submissive like the negros’. The Matranga brother’s and the

Provenzano brother’s Mafia domineered and the rivalry was on both sides for the

ruling of the <principal port district>.

In 1890 the

head of the police department of New Orleans was caught in an ambush and nineteen

Italians’ were incriminated. There was no sufficient proof, but some

journalists, who were at the hospital, heard the policeman murmur, just before

he died, <the dagos shot me>

(this was a contemptuous terminology used for <meridian’s>).

The trial kept

the nation on edge, the Mafia bosses, who had the best lawyer’s, were all

acquitted in March of 1891.

However, if

they had enough power to defend there picciotti

from justice, their bosses did not have enough to defend them from the

hatred of the people. Before they were freed, an angry throng of about ten

thousand people, led by the vice-mayor, attacked the prison and lynched the

prisoners: two were hung, two were killed by iron bars, others beaten by guns.

The bodies were hung from trees, and street-lamps.

Almost fifty

per-cent of the Union newspapers approved the massacre and the tension rose to

a point that Italy re-called it’s Ambassador from Washington. Other lynching

followed these in two other cities in Louisiana.

In the city of

New Orleans, torn apart by these implacable hatreds, Mother Cabrini arrived on

Holy Tuesday in 1892. She immediately perceived that she would have to begin

from the new generations, give a new semblance and another hope to those swarms

of youth that waited to increase the masses of the criminal underworld, and

compel the city to acknowledge the dignity of those humiliated and apprehensive

people.

She needed at

least an orphanage, a school and a boarding school, and at least fifty thousand

dollars to begin with.

Paradoxically,

in New Orleans a lot of Italians had made fortunes, they had become directors

of huge industries and owners of companies; but they did not like making

themselves known as Italians. They tried, in fact in every possible way to

forget their origins.

Frances went

looking for them, one by one: the Rocchi, shipbuilders from Milan, the Marinoni

from Brescia, bankers and owners of cotton plantations, Astrada, from Naples, a

famous proprietor of renowned restaurants, the illustrious clinic Formenti, Mrs.

Bacigalupo, a alimentary wholesaler, the Bevilacqua and Monteleone, owners of

luxurious shoe shops, and the millionaire Pizzati, Sicilian, of whom we have

already spoken.

These are only

some names that we wanted to mention, among many others, because they still

resound in our land; almost all of them understood and appreciated Cabrini’s

intent; it was to demonstrate to that city, (that loved and appreciated it’s

music, it’s artists, but hated the Italian people, considered either members of

the Mafia or potential delinquents), that the real problem was the social

indifference in which those youth were left, without any care or protection.

Saint Phillip Street’s orphanage became a social centre, for the children who were

boarded there and the hundreds of others who used it as an oratory, and also

for dozens of other children of every race and colour.

The chapel in

the Institute became the Italians Church and, in this case also, a proud and

orderly procession was held in honour of the Sacred Heart – in the old style,

that the population of New Orleans loved so much – to sanction a newly found

dignity; a procession with lots of religious singing, and even the “Va pensiero” that stirred even the white <masters>, even though jazz was the dominion in the city.

For the first

time the circles, the societies, the federations and the other small groups in

which the Italians were divided and lacerated, paraded together.

In 1905 an

epidemic of yellow fever hit the city. The emigrants of every race and colour,

in their ignorance, refused medicine, they infringed all measures of hygiene

and prevention, they refused to leave infected houses and buildings. France’s

nuns took on the task – going from house to house, risking their lives, and in

some cases really sacrificing it – in order to convince them of what they had

at their disposal for their well being.

Everyone

trusted the nuns, and – when the epidemic was over – not only the city of New

Orleans, but also the United States government and that of Rome publicly thank

them.

Let us return

to New York.

A part of the

life, in which the tragedy of the emigrants could have been touched by hand,

was the sanitary problem.

As they were

considered as human material, no one worried much about those who became ill because

of the inhuman conditions of life in which they lived, nor about the victims of

what was called <the industrial massacre> (hundreds and hundreds of

injured in their places of work), nor of the fact that hospitals where

emigrants could be admitted to did not exist.

There were

hospitals of course, where you paid, but even having the economical means, no

one wanted to go to them. What was the use for the sick that were not able to

make themselves understood when they tried to explain the symptoms of their

illness in that slang they mixed with their original dialect and the slang of

the American slums?

The patients

on having been admitted seemed to have entered a prison or an obituary, before

their time had come, everything was so cold and aseptic!, and they even lost

hope without a word of comfort from a nun or a priest.

They preferred

to die in their hovels, without care or cleanness, but having at least a little

tenderness.

Of course, the

Italians, if they had gathered together, they could have had their hospital;

the American government was ready to help them and the Italian government also.

They were not

at a loss for projects, and the argument was one of the furthermost in all

their dreams and discussions, but every tentative had miserably failed: a

hospital would have been needed for the Sicilians, one for the Neapolitans, one

for the Calabrese, on for the Lombards and so forth. Each and all were

concerned about their co-regionals, when they did not go as far as to stop at

their town fellowmen.

To tell the

truth, they had succeeded in opening a hospital <The Giuseppe Garibalidi

Hospital> - in the hope that the hero of the two worlds would bring them to

some agreement – but the general Commissioner for emigration had to admit, with

embarrassment, that inside that hospital <the Italian doctors argued twelve

months a year> and the money that had been collected to run the hospital

disappeared unexplainingly.

Frances felt,

with a certain discomfort, that all were looking and hoping in her, but she did

not feel able to take on that task.

Furthermore,

she had enough to think about, between schools and orphanages.

Then two

things happened that her conscience perceived as two voices – one from the

world and one from Heaven – both of them were asking her to obey God’s will.

The worldly

voce came to her by the news of two nuns that had gone to visit the city

hospital and one of them had heard a boy calling her, this boy had been in

hospital for some months, he stated to cry when he heard her speaking his

native language. He had a letter and had kept it under his pillow for three

months, he was illiterate and no one had been able to read it for him. The nuns

themselves had difficulty in reading the letter because it was written in very

poor Italian, however it brought the news that his mother had died suddenly.

For three long

months he had laid his head on this news without being able to give it a voice.

Frances cried

heart-brokenly. That night she dreamt – and it was the voce from heaven – of a

hospital ward in which she saw a fair and beautiful lady was walking among the

beds, with incredible tenderness, she caressed the ill and pulled up their

blankets. She immediately understood, in the dream (or vision, perhaps!), that

it was the Blessed Virgin and she rushed to help her. It was not her duty, the

Queen of Heaven, to serve the sick! But Our Lady – she was still dreaming –

looked at her somewhat sadly and said to her: “I am doing what you do not want to do!”.

The next morning

Frances had already decided to destine ten of her nuns to this task.

At first she

tried to take over a home that the Scalabrinians owned, but it was going

through a rough rime.

When she

realised that the running of the home would be very costly, she did a trick.

She rented two houses, bought some beds and put the nuns to work making

mattresses, and then, secretly transferred the patients (all of them with their

cutlery hidden under the blankets) and some bottles of medicine to the new

centre. The nuns would sleep on mattresses on the floor, using their coats as

blankets.

This is the

way – in 1892, the centenarian of the discovery of America) - the Columbus

Hospital started, with two

American doctors working gratis, amazed as they were by the courage of that

woman. The up keeping of the hospital was always guaranteed my thousands of

ways of charity that Frances knew how to find and keep coming in without

interruption, up until the financial state aids began to arrive.

In just a few

years the Cabrinians were known every where as <the Colombo’s Sisters>.

In 1896 six hundred and fifteen was the number of patients being treated

gratis; in the first thirty years of the life of the hospital one hundred and

fifty million patients were taken care of.

<But this is Italy!> exclaimed the

Italian Commissioner of government for Emigration, remaining speechless, on

seeing the meridian atmosphere that reigned in that hospital: he then waited to

be presented to Mother Cabrini, with the priggishness of an important person,

who had come to <take account of the situation and refer it to those of

authority>.

He was deeply

impressed by her penetrating, investigating eyes and of a species of

indomitable energy that emanated from that apparently fragile figure. He was even

more so, when he heard her say with a frankness that did not leave space for an

answer : <You all discus too much! It

is not necessary to discuss a lot on the necessities to protect the emigrants:

this is to be done! I do not discuss; I find that good must be done? I get

straight down to the task with my little Institute and I never despair in

finding the means, because I trust that in one way or another I will always

find them>.

Some years

later, that same Commissioner, who had become her friend and an enthusiastic

admirer, will say to her: <Mother

Cabrini, you do more for the emigrants than the entire Ministry for Foreign

affairs put together>.

In 1903 she build another hospital in Chicago, adapting a luxurious hotel bought for the sum of one hundred and twenty thousand dollars, when she had only ten thousand to lodge as a deposit, money that had been collected among the inter Italian of the city.

She left the

refurbishing to some of her nuns who were unfortunately cheated by dishonest building

contractors, who involved them in useless and badly done works, which caused

frightful debts.

|

|

Frances

returned ten months later, when all seemed lost. But she did not lose heart, she

sacked the contractors, architects and builders, and began again employing,

under her own personal command, new hosts of builders, carpenters, plumbers.

She came up against the

Mafia in

Illinois: she received threatening and warnings. In was during the winter when

they cut the water pipes, and so the ground floor turned into a thick sheet of

ice which took pickaxes to break, they burned the basements, they than

threatened to blow up the building using dynamite. When no one expected it,

because the works were not finished, she transferred the infirm to the

building.

Saying. <Let us see if they will blow up the

infirm”>. They left her alone. She had won once again and before leaving

was able to dictate regulation for the internal service of doctors and nurses.

She seemed

indestructible to a point that they had given her the affectionate nickname of:

<Sister perpetual motion>.

One day while

she was travelling on a train in Colorado, infested by bands of outlaws, the

train was attacked. A bullet penetrated France’s compartment and seemed to be

heading straight for her, but it swerved without hitting her: <They would not harm you even if they

shot you in the face>, a railway attendant said to her in admiration.

This was the real impression she gave every time she had to face difficulty or

danger.

We have to renounce telling many stories that strike our imagination just to mention them.

Here we have some principal names and dates.

In 1896: she founded

a college in Buenos Aires, where she arrived after having crossed the Andes

climbing to the height of four thousand meters on the back of a mule; 1898: she

opened three new schools in New York, a college in Paris and one in Madrid;

1900. Other congregations in Buenos Aires and a college in Rosario de Santa Fè;

a school in London and an Institute in Denver in Colorado; 1903: apart from the

Columbus Hospital in Chicago, she

started an orphanage in Seattle; 1905: she opened a orphanage in Los Angeles; 1907:

she founded a college in Rio de Janeiro, 1909: she opened another hospital in

Chicago, 1911: she opened a school in Philadelphia; 1914: an orphanage in Dobs Feny in New York; 1911: she opened

a sanatorium in Seattle. Not to mention the Italian foundations, the L’Istituto

Supeiore di Magistero in Rome, and a college in Genoa and Turin, all this

between one journey and another.

In all, in

figures: thirty seven years of activity with the foundation of sixty seven

institutes; travelling forty four thousand miles by sea (joking about her

country girls origins, Frances called the Atlantic: <The road of the

vegetable garden>, and sixteen thousand miles overland.

The figures

say nothing about the apostate of the Cabarin. It is enough to remember that

Frances conducted some of them to the mines in Denver, going down to nine

hundred feet in profundity, preparing them with accurate tenderness: <It

will not be difficult to speak to the miners about Heaven, saying that they are

already in hell>.

From then on

she destined some of her nuns to the service of those who <had no air or family>.

As she also

conducted other nuns to the Sing Sing prison, where a great number of Italians,

unable to defend themselves, like the ill who were not able to explain their

illnesses, they rotted in hatred and desperation.

The nuns were

occupied mainly in maintaining the connections – otherwise impossible – between

the prisoners and their families.

The prisoners

cried when they heard that Frances had desperately battled to obtain the

postponing of the execution of a boy, an only son, who’s wish was to see his

mother before he died and to ask her to forgive him for having abandoned her,

leaving her on her own.

Frances

Cabrini had helped her to come to America, paying her fare for the long

journey, accompanying that poor woman wrapped in her country woman’s black

shawl, with infinite tenderness.

We do not have

time to tell of the type of fibre that those intrepid nuns that Mother Frances

escorted with her, in groups that were ever growing in number, each time she

returned from Italy.

One episode is

quite sufficient to have an intuition: at the docks, while waiting to board the

ship for America, a nun was explaining piously to her relatives who had come to

say farewell: “I make this grave

sacrifice in going to America, willingly “. Frances, who was standing

beside her, suddenly interrupted her: “God

does not want to impose you with this grave sacrifice, my child, remain here”. And

another nun took her place.

Harshness? No:

realism. That same realism that never believed that anything was impossible,

was telling her that you could not undertake a task without devoting yourself

to it full of joy and without being completely detached from yourself, even

from your spiritual habits.

Therefore she

had a very precise pedagogical system: “When

I go to visit one of our homes and I see long faces, and note a certain aria of

depression, of listlessness and bad humour, I never ask anyone: ‘What is or

is not wrong with you?, I just start a

new activity that obliges the nuns to come out of themselves”.

God only knows what would happen, and how certain institutes would be renewed, if the respective superiors would find the courage to adapt similar pedagogical criteria!

One last thing we must say. Sometimes certain <laic> love to repeat with derision that <you cannot govern with Our Fathers>, and not even with the <social doctrine> of the Church.

Never the less, there are pages of history in which faith and prayer have demonstrated the capacity of such a concrete and multiform operate, of such a prompt social geniality (Sollicitudo rei socialis) and anticipator to make us certain that the lack of prayer – and furthermore the lack of a real faith – that leaves man in the most tragic egoism, in a moment when they want to govern their similars and invent recipes for social progress.

Above all an <intellectual> egoism, of a mind which inevitably is obliged to lose it’s time with one’s self and his own prejudices, and with his own small<condition>, for whatever extension he may imagine to give it. So, the necessary consequences, also an inevitable narrow mindness, in understanding the problems and in facing the needs, the narrow mindness of man void of the infinite breath of prayer and faith.

“The

world is too small, I want to embrace it entirely”, Mother Cabrini would say. And she did not fear – recalling certain

memories of school – to confess. “I will

never be in peace until the sun never sets on the Congregation”.

Non the less – with the same truthfulness

– she would say, as had many other Saints before her: “God is everything and I am nothing”.

|

|

The difference that came from her Holy Fathers, lay here: she desired to take her Congregation to the four corners of the world, so that the sun could never set on them, without ever thinking of herself or her projects, but only desiring to do her best in order that there would be no space whatsoever where that Christ she loved so much, would not shine on.

“Jesus

–a beautiful expression she used – it is a blessed necessity”

She believed everything was possible,

because she repeated with Saint Paul: “I

can do all in Him that gives me the power”.

To the Christians of that time and to

those of today she remembered: “Without

striving, you get no-where. What do businessmen not do in the world of affairs?

And why can’t we do almost the same for our beloved Jesus’ interests?”.

When, worn out by work and joy, in 1917, she died in Chicago, in the Hospital that she herself had founded, our emigrants said with affection and gratitude that the <Italian Columbus had discovered America, but only she, Frances, had discovered the Italians in America>.

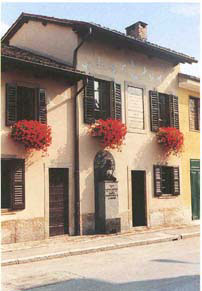

Monument

to St. Frances Cabrini

Divo Barsotti wrote properly: <Frances Cabrini’s life seems like a legend. A history of the Church that ignores this fragile woman is in grievous fault; an Italian history that refuses to speak of it is sectarian>.