Translator Antoinette

St. John Bosco

Passages from the book: RITRATTI DI SANTI by Antonio Sicari ed. Jaca

Book

Don Bosco was born just about 30 years after the French

Revolution, the same year in which, with the Viennese Congress, the napoleon

myth died (1815). During the preceding century, the so called <luminous

age>, faith had undergone attacks and mockery in a programmed offensive that

was conducted for a divined reason which pretended to be fighting against

everything that was called <superstition>.

Don Bosco was born just about 30 years after the French

Revolution, the same year in which, with the Viennese Congress, the napoleon

myth died (1815). During the preceding century, the so called <luminous

age>, faith had undergone attacks and mockery in a programmed offensive that

was conducted for a divined reason which pretended to be fighting against

everything that was called <superstition>.

In the X1X century the attack is

somewhat ‘confused’ and a mixture of social and national questions.

It is not possible, even if we try

hard, to describe the times of Don Bosco. They were times of the beginning of

industrialisation, of up rising, of restorations and revolutions; however times

of trouble which we cannot even dream or imagine. To make it easier, especially

for the younger generations, we can put Don Boscos name beside some of his most

prestigious contemporaneous.

When the philosopher Hegel died,

Don Bosco was sixteen years old. Comte – who will try to found the new

humanitarian religion – is seventeen years older than our Saint. Feuerbach is

eleven years older; Darwin six, Marx is five years younger, Dostoevskij six and

Tolstoj thirteen.

In Italy when Don Bosco is born,

Foscolo is thirty-seven years old, Manzoni thirty, Leopardi seventeen, Mazzini

ten and Garibaldi is eight years old.

Pious 1X, Leone X11, Vittorio

Emanuele 11, Cavour, Rattazzi, Crispi, Rosmini will be his friends.

|

House where Don Bosco lived from the age of two years old. |

In the same city and the same year

in which Don Bosco dies, in Turin, Nietzsche will become completely insane.

Many of these names Don Bosco will

never even know.

The most famous literate that Don

Bosco will meet, during two secret encounters in Paris, according to the

testimony of Don Bosco in person, was Victor Hugo, who he will convert.

Without doubt the world in which

Don Bosco lived was exactly that which was disturbed by all these influences.

It was in this world that Don Bosco made his chooses, cultivated certain ideas

and refused others, sometimes assuming superficial dogmatic impositions of his

times. It would be difficult to see him do otherwise.

In all this ribollition of people,

events, ideas, projects, restorations and revolutions – a time in which the

Church was sometimes considered an ally and more often an enemy to be

oppressed, and during which anticlergy touched unbelievable extremes – a

different phenomenon however is to seen, that which will make the heads of even

the enemies bow: piety. An abundant piety that especially of the so called

<evangelisers of the poor>, a piety that was transferred to the very

centre of a city in rapid evolution, a piety that will carry with it a flux of

overwhelming experiences and unnatural phenomenon.

You can take an episode in Don

Bosco’s life and examine it under a microscope to find an imperfect

documentation, and then in compensation there are immediately other thousands

sustained by dozens of testimonies of various kinds.

We can take, for example, as a

point of reference, the year 1848 that went down in history as the year of

great tribulations, the year of the war for independence.

In Turin, the seminary is empty.

More than eighty chierici in reaction to the Archbishop, during the Christmas

mass, locked themselves in the presbytery of the Dome with the tricolour cokade

on their chests, and in the same manner took part in the celebrations for the

Statute.

The following year, the Archbishop

is arrested and imprisoned. In the city the anti-clerical bands break out and

attack the convents. Priests are divided in two groups, patriotic and

reactionary. In the meantime, the government prepares a law to suppress all

convents. The law, which will suppress 331 religious institutes and a total of

4.540 religious men and women, is signed in 1855.

These are just some of the

terrible episodes among thousands of others; even though in these same years in

Turin, Don Bosco, Saint Giuseppe Cafasso (the priest of prisoners and condemned

to death, who is also Don Bosco’s spiritual guide), Saint Giuseppe Benedetto

Cottolengo (the priest of the incurably sick who was said to be the ‘the

Providence’s Manuel), lived and work in contemporary, friends and

collaborators. For a certain period of time Don Bosco will give them a hand,

then he will follow his destiny. One day, Saint Giuessepe Cottolengo, took the

hem of Don Bosco’s vestments in this hand and told him prophetically:

<It is too light. Get yourself a heavier vestment because many boys will

hang on to this habit. >

In 1864 Don Bosco will meet a girl

some twenty years younger than himself; St. Mary Mazzarello, who will found the

order of the Daughters of St. Mary Auxiliatrix.

In 1854 a boy of a rare interior

spirituality will enter the Oratory. It is the year of the proclamation the

Immaculate and this boy is in love with this Marian mystery. He is Domenico

Savio who becomes a Saint when only 15 years old.

Another very young boy who will

also become a successor of Don Bosco, and has recently been proclaimed

Venerable is Blessed Michele Rua.

Another boy, who will spend three

years at the oratory, <the happiest season of my life>, when he hears

that Don Bosco’s life is in danger he is only 16 years old, and offers his

young life to God in exchange. He will become Venerable Luigi Orione and he too

will found a congregation for poor children (he is the boy of whom Silone

speaks in one of his famous autobiographies). Speaking of Don Bosco he says. “I would willingly walk on burning coals

just to have the chance to see him once again and thank him.”

Another young priest, Don Federico

Albert, will preach his first spiritual exercises to fifty boys, from among

which Don Bosco will choose as his collaborators. Today that preacher has also

been proclaimed “Venerable”.

There are already eight Saints

officially recognised by the Church, not to mention the dozens of others who

will remain anonymous, who meet as friends meet friends, they talk and there is

an understanding between them. It is around them that the supernatural is

rooted with numerous and moving episodes, as though God meant to show that -

while the Church suffers for her sins and those of others and debates in

interlaced problems – the living blood that flows in its ecclesiastical body

and the Spirit that lives in its bodily heaviness.

In Don Bosco’s life very type of

miraculous phenomenon is present: prophetical dreams, visions, bilocations,

capacity to perceive by intuition the secrets of the soul, multiplying of

bread, food and hosts, healing and even resurrections of the dead.

I shall tell of two sole episodes,

which had a great effect on the public in the society of the times for the

first, episode is not only sad but also terrible.

When the King decided to sign the

law of suppression of all convents – a law that will be the cause of his

excommunication by the Holy See – Don Bosco <<dreamt>> that a court

page announced:

<Many funerals at court>.

He spoke of this with all his

collaborators. He wrote a letter to the King warning him “ to regulate himself

in order to avoid the threatened punishment and to avoid in every possible way,

that law coming to order”.

The following is a chronicle of

the facts. Don Bosco’s warning was in December 1851. On the 12th of

January 1855, the Queen mother, Maria Teresa, dies, at 54 years old. On the 20th

of January the Queen, Maria Adelaide, the king’s wife dies at the age of 33

years old. On the 11th of February, the Kings brother, Prince

Ferdinando di Savoy dies at the age of 33 and on the 17th of May the

Kings youngest son dies at the tender age of 4 months old. The king is furious

with Don Bosco. On the 29th of May, he will however sign the law,

advised to do so even by some priests.

Everyone judges as the may, but

the contemporaneous remain speechless.

Whereas, the other episode is

moving: in the summer of 1854 in Turin an epidemic of cholera breaks out and

its epicentre is in Borgo Dora, where the greater number of emigrants live, and

this quarter is just a short distance from Don Bosco’s Oratory. In Genoa alone,

in a month the victims will be 3.000, in Turin 800 with 500 deaths. The Town

Mayor will make an appeal to the city, but no volunteers to help the sick or

transport them to Lazzeretto will be found. Everyone is in a panic. On the

feast-day of the Madonna della Neve, the 5th August, Don Bosco

gathers his boys and promises: “If you

all remain in the grace of God and do not commit mortal sins, I assure you that

none of you will be touched by the plague” and asks them to dedicate

themselves to the assistance of the plague-stricken.

Three squads: the older boys in

the Lazzaretto and in the houses, the younger ones to gather the dying in the

streets and the sick who were abandoned in the houses. The smaller boys stayed

at home waiting and ready in case of urgent calls.

All of them with a small bottle of

vinegar to wash their hands after having touched the infected and ill. The

city, the authorities, even though anti-clerical, are amazed and fascinated.

The emergency ends on the 21st November. Between the months of

August and November, there have been 2.500 plagued and 1.400 deaths in Turin.

None of Don Bosco’s boys will be stricken by the plague.

These are only two episodes that

can help to perceive something of the atmosphere in which Don Bosco lived, as

something palpable, the boys and the collaborators who were with him, attracted

not by his ‘magic’ but by his familiarity with God. This is the way Catholics

reasoned. Who denies this by principle must then necessarily accumulate a

thousand and one alternative reasons for his denial. In 1884 when Don Bosco is

interviewed by a journalist of the Journal

de Rome (he is the first saint in history to have undergone this

journalistic technique by an American in 1859), and he will be asked, among

others, the following questions:

Q. Using what miracle could you as you have found so many

houses in as many countries in the world?

R. I did more than

ever I had hoped to do, but how I not know. The Holy Virgin Mary, who knows the

needs of our times, she helps us…

Q. Allow me to be indiscreet: you have made miracles?

R. I have never

thought of anything else apart from doing my duty. I prayed and I confided in the

Madonna…

Q. What is your opinion on the situation today in the Church

in Europe, Italy, and of it’s future?

R. I am not a

prophet. All you journalists are. Therefore, it is to you that we should ask,

what is going to happen. No one, apart from God knows the future. However,

speaking as a human being, it is to be said that the future looks quite

critical. My outlooks are sad but I fear nothing. God will always save his

Church, and the Madonna, who visibly protects the contemporaneous world, will

know how to rise redeemers.

So who was Don Bosco?

To speak of Don Bosco, we must

first speak about his mother: a poor peasant, who could neither read or write,

who had become a widow when John was two years old and who had to strive in

times of hunger and trouble to keep her family united. Her knowledge is

elementary: some phrases of the Scriptures learned by heart and the episodes of

the Gospel, the fundamental principles of a Christian life (“God knows our

thoughts”), heaven and hell; the redeeming value of suffering, a confiding

glance to the Providence; the sacraments and the Rosary.

|

Monument to

Margherita (Encrico Manfrini

1992) |

Let us

listen to what Don Bosco himself has to say. “I remember that it was she who prepared me for my first confession.

She came with me to Church. She first went to Confession herself, she

recommended me to the confessor and afterwards she helped me in thanksgiving.

She continued to help me until she believed that I was fit to make a proper

confession alone>.

Don Bosco continues: <On the day of my first Holy Communion in

the midst of a crowd of girls and boys, it was almost impossible to keep

concentrated. In the morning my mother forbade me to speak to anyone. She

accompanied me to Holy Mass. We prepared for Mass and afterwards gave thanks

together. That day she would not allow me to do any manual work. I spent the

time reading and in prayer. She repeated these same words over and over

again:< My son, this has been a very special day for you. I am sure that God

has become the Lord of your heart. Promise Him that you will do everything

possible in order to conserve your goodness for the rest of your life…>

And it is this same woman, when there is talk of a possible religious

vocation for her son, who will say: <If

you were to become a priest and unfortunately became rich, I will never set

foot inside your house>. And on the day he was ordained: <Now you are a priest and nearer to

Jesus. I have not read your books, but remember that having started to say Mass

means having began to suffer. From now on think only of saving souls and do not

worry about me>.

When she will have became a

grandmother to her other son’s children and was relatively at peace, John will

go to her and say: <Once you said to

me that if I had become rich you would never enter my house. Now I am poor and

full of debts. Would you come and be a mother to my boys? >.

Mamma Margherita will only humbly

reply: <If you think that this is

God’s will…>.

She will spend the last ten years of

her life (1845-1856) being a mother to dozens of children that were not hers,

but who are brought to her by her son priest on Gods willing, until worn out

and weary – she gathers strength from a humble and patient glance towards the

crucifix.

Saints are born and grow this way.

When he was very young, John had a

dream, which even during his sleep, seemed impossible: < to change “wild

animals” into God’s children> and from then an interior impulse drives him

to dedicate himself to poor and neglected children.

For them he became a priest,

studying later than was usual for priesthood but helped by a prodigious memory,

overcoming all kinds of humiliations and fatigues.

During his years as a student he

found the time – to maintain himself and because of his love of it – to be a

shepherd, a juggler and gymnast, a tailor, an ironmonger, a barman and baker,

he kept points at a billiard table, an organ and spinet player. Later on he

will become a writer and compose songs.

To worry about other boys, who

were without food, education and faith, seemed to him, as he himself writes - <the only thing he had to do on

earth>. And this <since I was five years old>.

|

Mamma Margherita |

Turin at the time was caught in

the fever of the beginning of industrialisation. The emigrants are thousands,

in 1850 they are counted to be between 50.000 and 100,000. Houses begin to be

built. The city is invaded by gangs of boys offering themselves to do any type

of work, peddlers, shoe-shiners, chimney sweepers, safety match sellers, stable

boys, errand boys… and they have no one to protect them. Gangs are formed who

infest the city suburbs, especially during the days of festivity.

The boys who Don Bosco approaches

in the beginning are builders, chiselers, pavers and such.

Many of these boys will turn to

robing and end up in the city prisons.

Other young priests will also

begin to look after these abandoned boys but they will be to taken up in

political problems that their work is overcome by these problems. One of these

priests – very well known in Turin – persuaded that he was following the

“people”, lead his two hundred boys to take part in the battle of Novara. It is

to be a failure.

Don Bosco is worried only about

his boys. He gathers them in the Oratory; he drags them along in the continuous

search of a suitable place, large enough to hold the large, ever-growing

numbers of boys. His battle is against a lot of problems. The politicians are

uneasy about the revolutionary potential represented by those gangs of youth,

who obey Don Bosco, in there hundreds.

|

Don Bosco with his boys. |

The Oratory is surveyed insistently by the police. Some “good

thinking” citizens believe that the oratory is a centre of immorality, the

parish priests of the city are anxious because they think that the ‘parish’

principle is being destroyed. If there is to be an Oratory, then this must be

in the parish. The accusation is <The youth fall away from the parish>.

Don Bosco is also accused: on the

other hand the parish priests still have ideas that are long past and gone as

far as emigrants are concerned, they still have the idea that these boys should

present themselves with letters of recommendation from their parish of origin

in order to be accepted.

The parish oratories that exist

are only for Sundays and Don Bosco has a different view of what an Oratory

should be, he wants them to be open every day under the responsibility of the

priest. Only this will be reason for the parish priests prudent suspension of

their judgement. They do however insist that Don Bosco will later send his boys

to their respective parishes.

But they are boys who would never

dream of going close to a parish, and moreover, a thing that is difficult to understand

for those who are standing on the outside and looking in, is that Don Bosco’s

Oratory is only a structure or a place. Substantially the Oratory is Don Bosco

himself, his person, his energy, his style, his educational methods and these

you cannot transport from one parish to another. Fortunately the Archbishop

decides to personally make a visit to the Oratory. He will spend a day full of

cheerfulness and thoroughly enjoys himself, <I have never laughed so much in

all my life>, he will say. He gives Holy Communion and then Confirmation to

more than three hundred boys, and is proud of so many young boys, even if in

suddenly standing up he will bang his head; he was wearing the mitre, on the

ceiling of the low building.

He decided to have the records of

the confirmations gathered by the Curia and subsequently sent to the boy’s

respective parish priests: and so the Oratory is practically accepted as “the

parish of the boys who have no parish”.

With a significant theological

underlining, Don Bosco says that Abbot Rosmini – his enthusiastic supporter -

<compared our work to the missions

that are opened in foreign lands>.

Another battle was against the

so-called patriotic priests>, who will try with all their strength to

politicise his boys, in order to engage them in the Renaissance battles.

<In the year 1848 – he

writes – there was such a perversion of

ideas and opinions that I could non-longer even trust my domestic help. So I

had to do all the housework. I had to cook, prepare the tables, sweep floors, cut

the wood, made shirts, trousers, towels, sheets and mend them when they were

torn. It seemed to be a loss of time but I found the occasion in these

activities to help the boys in their Christian education. While I distributed

bread, poured soup, I could at the same time, calmly give a wise and good piece

of advice, say a kind word”. >

On another side, the battle was

against those who (and they were many, at a certain point even his friends)

were convinced that Don Bosco was really and truly crazy.

While he and his boys kept moving

from one miserable place to another in search of a decent place to live, Don

Bosco keeps telling them with absolute conviction of vast Oratories, houses,

schools, churches, laboratories, thousands of boys, with numerous priests at

their disposition.

The boys believed him, they

repeated his words. On the contrary, even his dearest friends lost hope: <Poor Don Bosco, he has become so

infatuated by his boys that he has lost the use of reason>.

All of Turin spoke of the “crazy

priest”. They even tried to commit him, using a trick, to an institution for

the mentally ill. The Saints best friend a priest, in tears, says: <Poor Don

Bosco, he is gone crazy! > <Everyone

writes Don Bosco – kept his or her

distance from me. My collaborators left me on my own with about four hundred

boys”>.

The one thing that was the most

disturbing was, the fact that the reality of things was far from his

descriptions “houses, schools, churches, etc.” and exasperated they asked them:

<but where are all these things? >,

he replied: <I don’t know, but

they exist, because I see them>”.

Meanwhile the boys were growing

and becoming a greater concern.

<I must admit – Don Bosco

writes – that the affection and obedience

of my boys reached incredible levels>. This was only a further cause to strengthen the rumours that Don

Bosco, with his boys, could from one moment to another start a revolution.

We must come back to the political

atmosphere of the time. However, hadn’t this extraordinary man taken from

prison, on his promise and word and without surveillance, just for a day of

relief, more than three hundred boys, bringing them back in the evening without

even one of them missing? We must understand who Don Bosco was and meant for

them. One episode revels this quite sufficiently.

In July 1846, after a hard day’s

work at the Oratory, he began to cough blood and fainted. In brief, he is dying

and is given extreme unction. He will remain on the verge of death for eight

days.

During these eight days there were

boys who, working on scaffoldings under a scorching sun, will not touch a drop

of water, this was their way of asking God to save Don Bosco. They took turns,

night and day at the Santuario della Consolata to pray for him, after their

usual twelve hours of work. Some promised to recite the Rosary for the rest of

their lives. Others made vows to live on bread and water for months, for a

year, some of them, for life.

The doctors gave no hope for his

life and they said that he would die before Saturday. The coughing of blood

continued, but unthinkably Don Bosco recovered.

He will find his boys in a chapel

- pale and weak – and says: <I owe my

life to you all. From now on I am going to live it only for you>. And

spends the rest of the day listening to them, one by one, in order to make

things easier and make the solemn vows they had made to God in return for his

recovery, possible to keep.

It was not a romantic affection or

idolised, it was the fruit of a life spent in works and deeds. It is impossible

to describe them all. We can only limit ourselves to the description of some

dates.

In 1847, when hundreds of boys had

already began to frequent the Oratory, some of which do not know where to go

because they have no home to go to, will begin to live permanently with Don Bosco

and mamma Margherita.

The first “guests” will live in

the kitchen. They will be six at the end of the year, thirty-five in 1852; one

hundred and fifteen in 1854; four hundred and sixty in 1860; six hundred in

1862 until the number reaches eight hundred.

In 1845 Don Bosco establishes a

night school, with a medium of three hundred students attending every evening.

In 1847 a second Oratory.

In 1850 he founds a society of

mutual aid for workers.

In 1853 a laboratory for

shoemakers and tailors.

In 1854 a laboratory for

bookbinders.

In 1856 a laboratory for

carpenters.

In 1861 a printing shop.

In 1862 a workshop for

ironmongers.

Meanwhile, in 1850 a boarding

school for students is opened, with twelve students whose number will rise to one

hundred and twenty one in 1857.

In 1862 the Oratory will have six

hundred internal students and as many external.

Apart from the laboratories there

are Sunday schools, night schools, two vocal and instrumental schools with

thirty-nine Salesians who with Don Bosco had started a religious congregation.

In the meantime – the diocesan

seminary having been closed – he also looked after the sacerdotal vocations. At

the end of his life (1888), many hundreds of “new” priests will have come from

Valdocco, because they came from the poor social class.

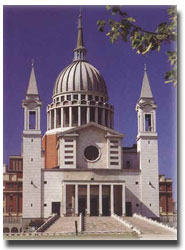

|

Sanctuary of Maria Ausiliatrice (1915-1918-Giulio Valotti,

architect) |

In the meantime, again – and

always for his boys – Don Bosco has become a writer: he writes a sacred history

for use in the schools, an ecclesiastical history, and a history of Italy, many

biographies and educational works. About fifty titles. He even wrote a small

volume on <a simple reduced decimal metrical system>: this new system

should have been brought into use by law in 1850 and became part of the

obligatory subjects in the schools starting from 1846, but the government had

not prepared the texts. He considered each small volume <an act of love>

for the Church and his boys. Another of his formation manuals for boys, quite

‘bulky’, reached its 118th edition in 1888. Up to now, we have

followed Don Bosco up to the beginning of the ‘60’s: a quarter of a century

before his death. By then he will have taken care of the publication of 204

volumes of a “An Italian Youth Library” (with texts in Latin and Greek), he

will have opened the first five colleges, founded a female congregation, built

the Santuario

of Maria Ausiliatrice and the

Church of the Sacro Cuore in Rome, he will have founded 64 Salesian houses in six

nations and missions in Latin America and will have 768 Salesians priests. He

will have made triumphal apostolic journeys to France and Spain, countries in

which everyone will want to meet <the man of faith> (the title by which

he is known world-wide).

He remains for four months in

France, in 1883, visiting as many towns as possible. When he arrives in Paris,

the Le Figaro writes that:

<outside his house lines of carriages have been waiting for the past week:

< Cardinal Lavigerie calls Don Bosco the Italian Saint Vincent de’ Paoli

>.

Another significant episode: in

1883 Don Boscos printing shop is the best-equipped in Turin. In 1884 at the

<National Industry, Science and Art Exposition>, Don Bosco had at his

disposal, a special gallery with the following sign in cubical characters:

DON BOSCO: PAPER FACTORY, PRINTING SHOPS, BOOKBINDING AND

SALESIANLIBRARY.

|

Don boscos temple (1961) |

He was the first priest to exhibit

in a national Exhibition dedicated to work. The historian who on reading the

sign, laughed, thinking he would find the usual bazaar of holy items etc., but

when he went inside to his great surprise he was amazed at what he saw. He was

able to follow the entire chain of work. It had never happened before to be

able to follow the process of paper making, from the beginning of the use of

rags to the production of the paper and finally the volume, with its hundreds

of illustrations and incisions and well bonded. A newspaper which was printed

in Reggio Emilia wrote that Don Boscos stand was one of the few that was always

crowded with visitors. This fascinating activity explains the question of the

real historical meaning of Don Boscos activity.

Today everyone is free, without

taking risks, to make brutal and banal judgements when they speak of the church

or anything regarding it, because many Christians accept and agree with them:

they are afraid of being triumphalistc; all criticism and depreciation of the

history suits them. Sometimes they go as far as lashing themselves; their want

of seeming to be ‘modern’ is so strong. In the case of exaggerating, they just

smile. In these 125 years of history of our nation, millions of Italians have

left these Salesian Oratories, formed in all senses. Millions of men will seem

to be pathetic according to the ideas of others, for the reason that Don Bosco

did not have advanced political positions or progressive social analysis

intellect.

He simply saw the needs and

intervened. His interventions were on real men, those who history produces

every day even though they may seem to be pathetic in comparison to the great

historical synthesis of the professors.

In a memorandum written by Don

Bosco to Francesco Crispi we read:

<In the register I see that no less than a hundred-thousand boys,

assisted, taken in, educated by this system, learned music, some literary

sciences, some trades and arts, and have become good artisans, shop assistants,

shop owners, teachers, clerks and more than one hold honourable posts in the

army. Many others, being naturally intelligent, can follow university studies

and obtain degrees in literature, mathematics, law, medicine, engineering,

solicitors, chemistry and so on>.

In front of Don Bosco some will

pull faces because they are in politics – in a complex and violent political

situation – these will prefer to abstain on one hand (it is quite enough “the

politics of the Pater Noster) and

on the other hand they choice the apparently easy principle to remain with the Pope.

In an epoch in which everyone – even the anti-clerical – acclaimed: “Long live

Pious 1X”, because their hopes were for a liberal Pope, Don Bosco taught his

boys that they should acclaim “Long live the Pope” instead. He was, using his

expression, attached to the Pope “like a polyp to a rock”. When questioned

about the Roman affair, so that he would take a position, Don Bosco answered: <I am a Roman Catholic, I am with the

Pope, and I blindly obey the Pope. If the Pope said to the Piedmont: Come to

Rome, then I too would say: Go. If the Pope says that the descending of the

Piedmont on Rome is a robbery then I too say the same. If we want to be

Catholics, we must think and believe as the Pope does”.

The people and the problems in

question, where not mythical as they are to-day in our history books: they

appeared as they truly were in all their ambiguity and meanness: On the other

hand, the part that those priests who politically sided with the <people,

for unity>, remains absolutely irrelevant in history.

Then again, Don Bosco was the man

on whom everyone, Church and State, King and Pope, statesmen and cardinals knew

they could absolutely depend on to find consent.

When it was necessary to resolve

the problem of the Italian dioceses after the unification (sixty dioceses had

no bishop) Don Bosco was the mediator during the long negotiations.

Another important episode. It was

the important statesman Rattazzi himself who spontaneously explained to Don

Bosco how to found a religious congregation, even if it was he who had ordered

the suppression of religious orders by the law he decreed (the famous Rattazzi

law of 1855). <Rattazzi – says Don

Bosco – wishes to combine, with me,

various acts of our Rule, regarding the way of behaviour respecting the Civil

and State Code>.

Practically he will with ability

show him how to form a congregation that will internally, be governed by the

normal ecclesiastical laws and which externally – respecting the State – be

governed according to the civil laws that regulated the different mutual aid

associations or other types. The genial intuition in <creating a religious

society that according to the State was a civil society> was given by

Rattazzi in person. The idea surprised even the Bishops themselves. It was born

from the natural affection that Rattazzi had, convinced anti-clerical though he

was, for Don Bosco.

Again faces are pulled, for Don

Bosco does not contest the social assessment of his times and the class

divisions, but helps the poor, thus remaining behind in this system. That is,

asking the rich for alms. This criticism means to think only on principles and

not on facts. Certainly, while Don Bosco founds his second Oratory, Marx is

writing the Manifesto.Don Bosco had

his own personal precise opinion on the situation, even though it did not

scientifically reflect on the international vastness of the pauperistic

phenomenon and the upheavals that were being prepared.

He refused to be a <social

priest> and politician because he felt that his vocation was immediate

intervention, love that rolls ups its sleeves and goes to work. There are those

who are called to fight against injustice and those who are called to

immediately fight its consequences. Everyone has his vocation: all are

important, that of who reflects and prepares analysis and projects to the

vocation of those who in the meantime have to love, to accommodate because the

poor cannot wait for the results of great analysis and great projects. <Let us leave to the religious orders who

are better formed than us, he used to say, the indictments, the political

action: We go directly to the poor>. Even Pertini wrote, that he had

learned in the Salesian schools <a

love that had no limits for the oppressed and the miserable: the admirable life

of your Saint was the model, which started this love in me>.

It is also interesting to know

that the first contracts of apprenticeship in Italy – a truly new social

revolutionary innovation – are written and signed by Don Bosco.

Another aspect that Don Bosco had up

to now ever been reprimanded. His educational capability. Nowadays there are

some who accuse Don Bosco of having used a <gloomy>, <regressive>,

<an almost obsessive pedagogical scheme> pedagogy.

Giuseppe Lombardo Radice, in 1920,

a famous anticlerical and faithless but honest, pedagogist, wrote to his fellow

men: <Don Bosco was a great man whom

you should you try to learn about. The church ambit, he succeeded in creating

an important educational movement, giving back to the Church that contact with

the mass media which it had lost. For us, who are not part of the Church and

also of all Churches, he is a hero, a hero of preventive education and of the

school-family relations. His persecutors can be proud of him>.

And again: >Don Bosco? The secret is in an idea? In our schools. A lot of

ideas. An imbecile can also have a lot of ideas, priest or not, master or not.

An idea is difficult, having an idea means to have a soul>.

After sixty years, those who

contest Don Bosco evidently have <a lot of ideas>. In 1877 Don Bosco

prints a short booklet entitled: “The preventive system in the education of

youth”.

Above all the first prevention was

the person of the educator, his absolute devotion.

<I promised God that up to the moment of my final breath that it

would be for my poor young boys – Don Bosco said. I study for you, I work for

you, and I am also willing to give my life for you>.

< Remember that for what I may be, I am everything for you, night

and day, morning and evening, in every moment>.

Prevention begins at this level of

the educators complete devotion, a devotion which Don Bosco meant in the real

terms of the word, to the point of demanding that the directors of his houses

remained with the boys at all times, even during recreation; they had to be

seen, perceived, encountered, familiar.

So, in an educational regime founded on authoritarianism, it was a

true revolution, an overturning of planning and had no need for

<coalitions>: it hadn’t as ideal well-formed queues but the gathering

around the educator.

In 1883 a correspondent for a

French newspaper “Pèlerin» wrote in

one of his articles:

<We have not seen this system in action. In Turin the students form

a huge college, in which queues do not exist, but the students move from one

place to another as in a family. Each group surrounds their teacher, without

being noisy, patiently, without contrasts. We have admired the serene faces of

those boys and we could not keep from exclaiming: God’s finger is here>.

Cheerfulness must have been the

natural spring that joined the supernatural: < You must know – young Domenico Savio explained to a newly arrived

companion – that here we make piety consist in being cheerful>.

The imposition had to be abolished

even where it was consecrated from the use and importance of the matter: at the

time there were no educational environments for youth in which confession and

Holy Communion were not obligatory.

Don Bosco confessed and

communicated all the boys, but no one was obliged to do so. In fact he always

recommended that they were not to be bored by obligations. He only encouraged

them. Simply showing them that, without peace of heart they could not be truly

happy, real boys.

On the other hand, Don Bosco was

deeply convinced that without intimacy with God, without <religion> it

was not possible to educate.

<Education, he would say, is a thing of the heart and only God is

the master and we cannot do anything if God does not give us the key to these

hearts. >. And added. <Only a Catholic can apply with success a

preventive method>.

He succeeded in convincing even

some protestants who went to visit him for lessons of this. The expressions

that may seem <intolerant> are part of that total “idea” which makes a

true educator. Don Boscos idea of a true educator is total, total is the idea

of his activity, and total is his idea of the need for education.

There is not one single aspect

that he neglects or thinks unworthy of the educator, let this be in the menial

work of cooking, in the cutting of a suit, in taking part in a game, in teaching

a trade, or instruction, playing music, praying or preaching confessing or

giving Communion.

In 1884, while the saint is still

alive, an autobiography of Don Bosco is published, written by a French writer.

It says. <Up to now the founders of

religious Orders and Congregations have proposed a special project in the bosom

of the Church they have practised the law that the modern economists call the

law of the division of work. Don Bosco seems to have conceived the humble idea

in having all the work done by his humble community>.

Reason, religion, lovingness were

the trinomial on which Don Bosco intended to found his preventive work.

It was necessary to offer the

educator the entire space of live. Above all – lovingness had a particular

co-notation. You can in fact love a lot but conclude very little.

Don Bosco writes in one of his

famous letters from Rome in 1884: <My boys are not loved enough? You know

that I love them. You know how much I suffered and tolerated in the course of

forty years e how much I still tolerate and suffer for them. How many

sacrifices, humiliations, how many oppositions, persecutions just to give them

bread, houses, teachers, and especially to make them healthy.

I did what I was able to do and

could do for those who are the love of my life…What therefore, is needed? >

The answer was <That the boys

not only be loved but also that they themselves know that they are loved>.

In Don Boscos times this was so true

that one of his boys – as an adult – answering those who asked him said: <We

live by love>.

This was the genius of Don Bosco:

it was not enough to love, but you must show you love, make it be perceived.

<A love that is expressed in words acts and even in the expression of the

eyes and face>.

This requires a profound practice,

a total and daily involvement.

In 1883, one day a Lombard priest

goes to visit him, curious about what he had heard about him. He will become

Pope Pious X1, he who will proclaim Don Bosco a Saint.

He had to wait to be received,

because Don Bosco was at a meeting with the directors of his houses and was

speaking to them. Meanwhile the priest observed. Almost fifty years later –

about to become Pope – he would retell of the encounter:

<There were people coming from everywhere, who with one type of

difficulty who with another. And he on his feet just as if it was a question to

be resolved in a moment, listened to them all, understood and remembered

everything that was said, and then answered them all. A man who was paying

attention to everything that was happening around him but at the same time

seemed not to care, as if his thoughts were elsewhere. And it was truly so: he

was elsewhere, he was with God. He had the right word for everyone, something

marvellous. This was the life of sanctity, of continuous prayer that Don Bosco

lived among the never-ending worries and implacable>.

This was indeed an educational

potential – both on himself and on others – having become sanctity.

During the last months of his life

he was weak and walked with difficulty: <Where are we going, Don Bosco?>

they would ask him. <We are going to heaven>. he answered.

He was canonised at the closure of

the Redemption year, on Easter Sunday, 1934. He was the first Saint in history

to whom the State also, the day after his canonising, paid homage by a speech

in Campidoglio by the Minister of Education. This was a further acknowledgement

of how much Don Bosco really belonged to everyone. Up to today.