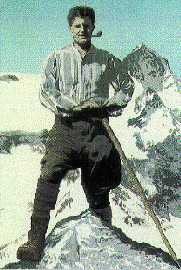

Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati

part of the book:

RITRATTI DI SANTI by Antonio Sicari Jaca Book publisher.

It has been recently necessary a Bishop's synod and a Popes document,

(Christifideles laici) to try to define the identity of the Christian laic, but

this identity has not been cleared in the intelligence and conscience of all.

Actually when this "identity" topic comes up, a mixture of sentiments

and resentments have been noticed, everyone is afraid to see his cultural,

social, party-political and even "ecclesiastical" belongings in a

light of crises (seeing that regarding this particular topic the Church is

still painfully divided). I'll try to

show here the trouble with simplicity, using only a brief formulation: this

century, starting from the first fundamental twenties, put more and more

emphasis on sad evidence than on dechristianization, which everybody talks

about, and doesn't give much regard to the moral deterioration of the way of living,

as directly the faith (here is why the Pope often speaks about the need for a

"new evangelisation"): the undoing regards the Christian popular

subject that, as such, doesn't feel more responsible (socially and globally

responsible) of the truth of Christ and of the truth that Christ is.

It has been recently necessary a Bishop's synod and a Popes document,

(Christifideles laici) to try to define the identity of the Christian laic, but

this identity has not been cleared in the intelligence and conscience of all.

Actually when this "identity" topic comes up, a mixture of sentiments

and resentments have been noticed, everyone is afraid to see his cultural,

social, party-political and even "ecclesiastical" belongings in a

light of crises (seeing that regarding this particular topic the Church is

still painfully divided). I'll try to

show here the trouble with simplicity, using only a brief formulation: this

century, starting from the first fundamental twenties, put more and more

emphasis on sad evidence than on dechristianization, which everybody talks

about, and doesn't give much regard to the moral deterioration of the way of living,

as directly the faith (here is why the Pope often speaks about the need for a

"new evangelisation"): the undoing regards the Christian popular

subject that, as such, doesn't feel more responsible (socially and globally

responsible) of the truth of Christ and of the truth that Christ is.

As a consequence, having not paid enough attention to this, having neglected

that faith, received as a gift and became culture (impregnated the soul of

society itself), every other effort of ethical restoration and of charitable

engagement couldn't prevent the dechristianization of our people.

The tragedy consisted in this: that which

was exploding like charity and apostolate (just think about the huge work of

the laic volunteer service, the numerous socio-political engagements of

Christians and all charitable engagement by religious congregations) was

systematically blown away from a progressive loss of faith of all the Christian

people without appreciable distinctions (devastating even the

"religious" and "theological" world itself). These are

historical contradictions on which one often obstinately refuses to give an

answer, let this be for a sort of guilty complex that one prefers to censor.

The most pathetic attempt of remotion is

the one of those who wants to attribute this "defeat" to a necessary

purification action: that is that Christians had to learn to distinguish

between Church and world, nature and grace, faith and reason, ecclesiastical

vocation and laic vocation, Christianity and politics, etceteras. We can't

demonstrate here the suicidal insubstantiality of these explications and

apologies become common obstinate patrimony. These also provocated paradoxical

attempts: there are those who look among the saints for some "champions of

Christian laic", but when one thinks he has found them he is then forced

to manipulate them in order to coincide the life and experience of this new

saints with his ideologically prefabricated distinctions. If one goes then to

look at the facts one notices that of many distinctions, having become a

fashion today, these "saints" are completely unaware, in fact they

cheerfully ignore them. And that their life is a continuous objection of who

believes that "Christian laic" means to realise wise equilibriums and

wise transfusions between world belonging and Church belonging. This is what we

saw with regard to Saint Giuseppe Moscati, it is what happens with Pier Giorgio

Frassati, who became Venerable on May 20th 1990. One of the most recent

biographies that were dedicated to him practically ends with these words: "Pier

Giorgio simply behaved like a laic in the Church and like a Christian in the

world".

Four crossed concepts to existentially

place only one person, who moreover would be very amazed by such language. The

truth is that the young Frassati reveived his "Christian laic" in a

way that is exactly at the antipodes of what some people that introduce

themselves as heirs of his "memoirs" would mean or would prefer. We

have no choice but to tell, going toward the proof of the facts, which

demonstrate with disconcertment evidence that the term "lay" and the

term "Christian" are equal in a absolute manner for the baptised

person, when this man hadn't received a particular ministerial or special

consecrated vocation, which require being further précised. Pier Giorgio was

born in Turin on Holy Saturday, 6th April 1901 in a rich middle-class family of

liberal stamp: his mother, Adelaide Ametis a well known painter; his father,

Alfredo Frassati, in 1895, when he is a little older than thirty-six years old,

founded the Italian newspaper La Stampa; in 1913 he is the youngest senator of

the Kingdom and in 1922 is the Italian ambassador in Berlin. In short the

Frassatis are at that time one of the three or four family that count in that

Turin that is changing in a metropolis rich of industries and subject to

massive workmen immigrations. But if the family situation from the point of

view of the social prestige is comfortable and stimulating, it is, instead, sad

from the point of view of the bonds of affections. Mother and father live a

difficult and very formal life, a facade kept only for dignity and for their

sons: dad is always busy "somewhere else", among the big troubles of

the newspaper and public life, mum repays herself with brilliant social

relationships and with a rigid and cold educational system. Witnesses define

her as a "modern woman, in advance of the times for her extreme ideas of

liberality".

Liberality that doesn't regard her sons:

Luciana, still living sister of Pier Giorgio, tells that their childhood never

lived indeed, spent a "badly defined nightmare in that huge gentlemanly

house that sometimes seemed "a sad barracks". During decades it's

been trendy to present this saintly university youth as a model of freshness

and purity, full joy of life, of physical and spiritual rigour and of rich

generosity towards the less privileged, as well as of impetuous socio-political

engagements. But the aspects of passion and crucifixion are been neglected and

silent (those alone permit to live like "risen") that is on the daily

background of his life and dead. Let's come back for now to the beginnings of

his spiritual itinerary. His family passed on to him most of all a system of

rules and duties (that is not actually evil, but can be rather sad), a system

that through his mother referred to the comprehension of life as generally

Christian, while through his father referred to a natural goodness, but void of

faith. Pier Giorgio absorbed Christian life immersing himself, spontaneously

and by personal choice, in the living water that the Church of that period

offered him: of that Church, in which limits and troubles were not missing, he

felt "part", an active member, attached to a vine like the Gospel

says, in which good sap flows. One could be surprised listing all the

"associations" to which Pier Giorgio wanted to be part of, often

against the opinion of his family, participating actively and taking on

responsibilities.

The names of these associations can seem

today disused and pietistic, but they mustn’t make us forget that at that time

they show the living cores of a Church in ferment: Apostate of prayer,

Eucharistic league, Young worshippers university students association (with the

engagement of nocturnal adoration every second Saturday of the month), Marian

congregation of the third Dominican order, and others. And these are only a few

belongings through which he educated himself most of all to prayer, that means

to possess a Christian heart, a memory, a wish, an absolute "mendicancy"

of his being. We could dedicate ourselves to describe the practices and

engagements that those associations involved, but the most important aspect is

in observed that his person didn't loose himself and didn't shatter in thousand

little pieces or in thousands devoutness, but was structured integrally so as

to not leave empty, weak, or petty spaces. Most of all, everything had a

centre: daily Communion. "Are you a over-devout?” somebody asked him one

day at the university (believers were insulted like this at that time, from the

Masonic-liberal, fascist, and social-communist". No, Pier Giorgio answered

giving back the hit with goodness, but with as much firmness, no, I remain a

Christian!” All that prayer generated in him a sure passion for all reality

indeed and he, with the same intensity, lived the duty and the pleasure to

belong equally to cultural, sporting, social, political associations, until

that "popular party" that was becoming like whisper for the

engagement and the identity even the political ideas of believers. In 1919,

still under age, Pier Giorgio signed up to the university club "Cesare

Balbo", that included also a "Saint Vincent conference". Here is

the description some members give of the ambient: the club was from my point of

view mouldy and not very interesting and the presence was most of all justified

by being able to play bar billiards. And another: As at the "Cesare

Balbo's" as at the catholic residence where we used to live, there were

lots of good guys, but hundreds of them at least didn't do anything else but

speak about adventures with girls while others, false and over-devout, appeared

to be ‘could have been’ clerics. It's a good description of why we assisted

during passed decades to the collapse of a kind of catholic association and to the

revitalisation of a big part of parish oratory.

Frassati and some friends decided

therefore to take in hand the circle. In a flier of auto propaganda they

proposed themselves as responsible: Students! Do you want to modernise and give

new blood to the circle? Do you want it to live above all its life and as an

audacious Christian over every rancidity of the fifteen-century and pigtail?

Submit the fates of it to the following colleagues: Borghesio, Oliviero...

Frassati. That recent biography which we have mentioned, explains that Pier

Giorgio was then with the most progressive and bore this testimony: He was

always on the opposition, he didn't understand half terms, bland measures,

diplomacy, also necessary sometimes to direct a boat with so numerous a crew

and difficult as that of an university circle. He was an extremist, it would

have wanted exactly to apply the Gospel and sometimes he was a little rough and

angular. He didn't admit deviations, the arrangements were contrary to his

character and he was not a malleable one.

Mystery of the words: today people of this kind are defined "reactionaries

and fundamentalists".

Pier Giorgio is made to pass instead as a

"progressive". This is not enough for hiding an evident fact: that he

has not been really an example of " laic" in the sense in which this

value is spread and publicised today. It is the case therefore to sift well

this typical "progressivism" that one is prepared to recognise only

towards saints. We have a series of episodes available. In the September 1921

in Rome the national Congress is held of the Italian Catholic youth, in the 50°

anniversary of the foundation. There are more than young people present. The

Sunday mass of September 4th is anticipated to the Coliseum, where

the teams converge coming from all over Italy: every group with its flag. But

the liberal-Masonic Police headquarter kept watches on horse in order to

prevent the celebration and the young people were forced to return to S. Pietro

Plaza, where the celebration could take place on the church square, followed

then from a hearing in the gardens. When the young people in the Vatican

decided to go to the ‘Altare della Patria’ singing the alternate song of"

Brothers of Italy and "We want God", the Police headquarter decided

again to disperse the procession using force. Here is a testimony that concerns

our young "saint"; Pier Giorgio holds up the tricolour flag of the

Caesar Balbo club. Suddenly they emerge from the front door of the Altieri

Building, where there were set aside, about two hundred regal watches to the

orders of the most sectarian police officer that I have never known. Cries:

" Set with the muskets, remove the flags!” It seems that they have to deal

with beasts. They beat with muskets, they grab, they tear, and they break our

flags. We defend them, as we are able with our hands and teeth. I see Pier

Giorgio taking on two guards that try to tear the flag from him. ... They push

us into the courtyard of the Building that is used as a safety room...

Meanwhile in plaza of Jesus the bestial show continues... A priest is thrown

literally on the courtyard with his cassock torn and a bloody cheek. To our cry

of protest they again set with the blows of muskets... Together we knelt on the

ground, in the courtyard, when the torn priest lifted the rosary and said:

" Boys, for us and for those that have struck us, let's pray!” The

magazine Catholic Civilisation, in a time when things were called by their

names, telling the facts explained them this way: " The sect, furious from

such an unexpected demonstration of faith, wanted to make blackmail of

it". And still: "The fact, owed to turbid intrigues of sect and

party... ". And it defines the distorted chronicles that the Newspaper of

Italy and the Resto del Carlino made the work of "certain journalists more

ignoble and more sectarians". The day after young Catholics had to go

themselves to S. Peter's again and Pier Giorgio with his guys recrossed the

city bringing in triumph the stubs of broken and torn flags to which he had

hung a great poster with the writing: "Tricolour slashed by order of the

Government". A "progressive" fact, as we see. However it was

spoken of all over Italy.

A

friend of Pier Giorgio tells: While everyone was speaking of him, he showed

reluctance to the congratulations that came from every part. Those praises

seemed strange to him because he could not understand as a young Catholic that

circumstance could act in different way. The following year the law was

declared that prohibited religious teaching in schools, just when at Catholic

associative level we complained of the "deplorable disorganisation"

of the students. In Turin Pier Giorgio wrote a letter to the partners of the

"Militias Marie" club, which he belonged to as delegate of the

students. He wrote: Our young people need a proper education for their strength

and a solid apologetic base to face the continuous dangers, to which they are

exposed while unfortunately attending corrupt public schools ... We who by the

grace of God are Catholic we don't have to waste our lives... We have to temper

ourselves to be ready to sustain the struggles that we will certainly have to

fight for the conclusion of our program.

Pier Giorgio expressly asks:

"continuous prayer "," organisation and discipline","

"sacrifice of our people and of ourselves" and he offered the

possibility of "after school activities where (the students) will complete

the culture that the public schools are not able to give, they will be educated

at the same time in the religious and philosophical matters". He concluded:

While I am thanking you for what you will do, sure that you will be compensated

largely in life, I greet you as a Christian. Hurrah Jesus! The students'

delegate. Pier

Giorgio Frassati. At to end of that same year the FUCI

exposed in its glass showcase at the Polytechnic the notice for a night-time

adoration of the Eucharist. Evidently the notice "stuck out" among

the thousand motley notices that, in the other glass showcases, spoke of

dances, parties and funs, and so the anticlerical ones democratically decided

to tear them and the voice scattered. A friend tells: I remember Pier Giorgio,

upright in front of the glass showcase with a baton in his hand, and a howling

uproar among the one hundred students. Insults, threats, struck they weren't

able to shift him. The greater number however, had the upper hand.

The glass showcase went into pieces and

the notice was burnt. However the destruction of the glass showcase and the

notices had become a vice, since the anticlerical ones punctually entrusted the

Giordano Bruno's club. More than a "forge", already, spoke about the

necessity to maintain good relationships and to begin negotiations. Frassati

didn't allow half terms: "I shall fight. Do we not have the right to

defend ours glass showcase, or do they only have the right to break it? The

others sustained that it was not possible however to stay there to continually

keep watch, but Pier Giorgio was hasty". I say that it is needed in order

to give a lesson". In another occasion, for the Easter parties, he had

posted a sacred notice in the courtyard of the university. They tore it. Pier

Giorgio copied it by hand and put it up again "with geometric

progression", reaching the number of 64 copies. Since the beginnings of

1920 when the nervous workers started, he accompanied them as a body guard, in

the red suburbs in Turin, a Dominican monk that went to talk to the young

workers”, among howling and threatening Bolsheviks", and not rarely, to

defend him, it ended up coming to the hands. In times of political elections he

spent entire nights driving a car full of manifests, fliers and printouts and

holding on the running board two big overflowing pots of glue, and

"attaching" in the most ‘hot’ points of the city, not without

undergoing aggressions and organised defences. And it will certainly not be

fun. When they instigate the fascist teams, the opposition of Pier Giorgio will

be so determined that his same house will be aimed at: on a Sunday, while he is

having lunch alone with his mother, a team storms into the house, armed with

batons of lead balls covered with leather, and start to smash the mirrors of

the antechamber and any furniture they come by.

Pier Giorgio succeeds in grasping a baton

and sent them running. Even the foreign

press brings the news of the episode. In a letter Pier Giorgio himself tells:

Dear Tonino, I’m writing to reassure you: you will read in the newspaper that

we have suffered a small devastation in the lodge from some of the fascist

pigs. It’s been more an exploit of cowards but nothing more... They have no

shame: after the facts in Rome they shouldn't let themselves be seen but be

ashamed of being fascist. In another occasion to who attacked him he shouted:

Your violence cannot overcome the strength of our faith, because Christ doesn't

die. He suffered basically because he began to discover the weakness of that

"popular party" in which he had believed. He was already enrolled to

his foundation and he publicised it without fear. He was convinced that

"the party would have been really popular when big numbers of faithful to

the Christians professional organisations had sustained it».

A friend tells that, when Pier Giorgio

spoke about it, he showed his love for it, because "it felt that it was a

social result of his faith". With the beginning of fascism he was

humiliated by having to ascertain the weakness and the changing of many

adherent of the popular party, but unlike so many he tenaciously stayed

attached to it "with the last hopes, with the last thoughts, with the last

wishes". When the Manager of the’ Popolo’, Giuseppe Donati, had to leave

in exile, only Pier Giorgio was at the border to say good bye and to shake his

hand, challenging the eyes of the fascist police. Donati in person then wrote:

" I saw in him the last friend of the Country that I left". And Pier

Giorgio would be dead three months later. From the social and political point

of view he was afflicted by the scarce intelligence of faith of many members of

the Catholic associations: that is the lack of the view of faith applied to

reality with intelligent love. In 1921, participating at the national congress

of the FUCI in Ravenna, he had proposed and defended the thesis of the breaking

up of the FUCI to make it meet it in an ampler "Catholic youth" that

united intellectuals, workers, students and simple people. He found opposition

in the ecclesiastical assistant of the FUCI, but he didn't show it had been

understood. He frequented the most vigorous club of workers, such as the "Savonarola", composed of metal

mechanics workers of the Fiat, well situated in front of one of the more

trained communist clubs. We brought, a friend tells, to the centres of

religious, cultural, social and syndicalism associations... Everywhere, it can

be said, Pier Giorgio was present and he co-operated and participated in every

initiative... He wasn’t even missing at the club of the Legionaries (of

particular importance, if one thinks that the First World War had shortly

ended) and at the Union of the Job, where the students met the workers.

Christian identity was for Pier Giorgio opened to all ambits, social and

political, even beyond the national borders. He was indignant because France

ruined "the most Catholic part of Germany"; militarily occupying the

Ruhr ("it's an infamy!” he said) and he wrote a letter of protest to a

German daily paper. In the same way he sustained with public declarations the

struggle of the Irish people that asked for " Independence of its nation

and its spirit." He had become interested in the international association

Pax Roman that united the university Catholics of all nations; and he wanted to

be the organiser of a conference that he held in Turin. All these indications

must not make us forget that we are speaking of a university student with

continuous and difficult examinations to be undertaken and overcome with at

least good results, but after strenuous work. To succeed he had to applicate

himself for a long time, and he wasn't exceptionally gifted. Yet even his study

was illuminated by charity and faith, if one thinks that among all the

possibilities that were offered to him, and they were notable, given his social

condition, he had preferred to enrol himself in the faculty of mining

engineering, because during his sojourn in Germany he had ascertained the

particular gravity of the conditions of work of the workers of the sector:

" "I want to help my people in the mines and I can do this better as

a laic than as priest, because priests here are not in contact with the

people". This was the way he explained the field of his studies that he

had chosen to Louise Rahner, the mother of the famous theologian, in who’s

house he sojourned for a certain time. He said he wanted to become "a

miner among the miners". There is another aspect of his life that we have

to describe, a more known one, but that now, in the amplest picture that we

have delineated, it finds its correct position. It deals with that "

voluntary service of charity" to which Pier Giorgio constantly devoted

himself, emerging himself in the liveliest tradition of the social saints of

his country (Don Bosco, Cottolengo, Faà di Bruno, Murialdo, and

Orione). Here is a delineated sketch from G. Lazzati, to commemorate the 50°

anniversary of the birth of Pier Giorgio: Estranged the men, beginning from his

relatives, they will see this youth to whom nothing seemed to be missing in

order to be a champion of worldliness (...) to drag through the streets of

Turin wheelbarrows full of the poor mens household implements looking for

houses, and to sweat under the load of big packages also badly packed, and to

enter the bleaker houses where poverty and vice go together, under the

hypocritically scandalised eyes of a world that does nothing to help them

better themselves; and to make himself, with amazing humility, he, the son of

the Italian ambassador in Berlin, he, the senator's son, solicitor for the

poor, and for them to remain without a cent for a tram to get back home, but

returns home at all hours of the night... His sister Luciana has revealed that

the situation was more humiliating than can be imagined: at home Pier Giorgio

passed as a fool and they kept him short of money: to be able to give to the

others, he often had to deprive himself not only of the superfluous but of the

necessary. What he did for the numerous poor families, of whom he took care of

as a member of the "Saint Vincent", results from thousand of episodes

full of charity and from thousand thankful testimonies. It was not therefore, a

dull charity: "to give is beautiful he said, but still more beautiful it

is to put poor men in condition to work". He knew well that charity was a

matter of social justice indeed". It was discussed; a friend narrates, of

certain agricultural pacts. He sustained that the land belongs to the farmers

and it must be given to who works it. Impulsively I exclaimed: 'But you that

owns fields, would you do it?’ He looked at me and he told me in few words:

They are not mine...I'd do it immediately!».

The conscience, with which meanwhile he

acted, lightening, as he was able to, the misery of the poor, with his own

sweat, emerged when he had to convince others to participate in his exploit. A

friend tells: One day he tried to convince me to take part in the "S.

Vincent". My difficulty was that I didn't have enough courage to enter the

dirty and malodorous houses of the poor, where I could catch some illness, he

in all simplicity answered that to visit the poor was like visiting Jesus

Christ. He said"; around the crippled, the miserable one, around the

wretch I see a light that we don't have...” that visiting poor men hovels was

possible to get some serious illness was not a way of saying. And in fact Pier

Giorgio became ill in a terrible way: despite that he was physically tempered

by sport, he contracted fulminating polio during one of his "visits», that

killed him in a week. It was a week of passion. Before briefly telling this,

let's see the image again that has been handed down of this university youth:

"bourgeois", open, healthy, jovial, a passion for the mountain and of

skiing, noisy at parties, animator of a healthy goliardy (he had founded a

" Society of the Left Types" with a proper statute). All of this was

not just appearance but in his nature. Yet, this same nature, without

dissociation’s, without highs and lows, without changing of character, it was

also deeply tempered by his and others suffering. Among them a lacerating

suffering, we have also to remember the deep love for a girl of humble

conditions, love to which he morally felt forced to abdicate when he realised

that his choice, for the prejudices of the family, it would have never been

approved. He understood that a possible insistence of his would have provoked

the definitive breaking of the bond between him and his parents. God suggested,

in the depth of the heart (and we owe to interpretative the episode considering

his entire brief life; without knowing it, Pier Giorgio was already a step away

from death) not to seek his happiness at the price of the salvation "of

his parents": " I cannot destroy a family, he said, to form another

one. I will sacrifice myself".

On June 30th 1925, returning from his

usual turn of charity, Pier Giorgio started to accuse migraine and inappetence.

Nobody minded him: in those days his old grandmother was dying, and that big

guy tall and muscular, who no one ever minded or took notice of because he was

such a good person, with his inopportune fevers was just annoying. Pier Giorgio

started to die, feeling his young body being destroyed, while the progressive

and implacable paralysis advanced, without anybody minding him. The dying

grandmother continued to polarise the attention of the family, causing physical

tiredness and psychological wearing out of all the family. Pier Giorgio was

kindly made to understand not to annoy them with his slight illness, when there

were already enough troubles in the house and when he would have done better to

study for his last examinations that had been dragging on for too long. So Pier

Giorgio, humble and obedient, faced alone the symptoms of this terrible

illness, the gravity of which he didn't entirely realise, and the agony of what

was happening to him, without even being able to speak of it, since every

attempt to do so was stopped with unknowing cruelty. When the petrified parents

realised what was happening under their eyes, it was too late. The serum made

hastily and exceptionally in the Pasteur Institute in Paris arrived when it was

too late to be of any benefit. On the last day of his life, Pier Giorgio asked his sister Luciana to

take a box of injections that were in his study to one of his poor men because

he had not been able to do so, he wished to write the necessary indications and

address. It is a note that visually expresses the tragedy: he wanted to write

it, at all costs with his own hand which was already tormented by the

paralysis, and an almost inextricable tangle of lines and letters are the

results. It is his will: his last energies for his last act of charity.

The funeral was a hasten of friends and in

particular of poor men; the first to remain astounded, to see so many that

loved him and so many he had known, it was his relatives that for the first

time understood where Pier Giorgio had really lived in his short years of life,

despite he had a comfortable and rich house to which he used to return to, never

on time. The most unusual and unexpected commemoration post mortem is the one

that the famous socialist Phillip Turati dedicated to him. He wrote in his

newspaper: He was really a man, that Pier George Frassati, that death seized at

24. What we read of him is so new;

unusual that it fills with reverent amazement even those who didn’t share his

faith. Young rich, he had chosen for himself work and kindness. Believer in

God, confessed his faith with open demonstration of cult, conceiving it as a

militia, as a uniform that is worn in front of the world, without changing it,

with the usual suit for convenience, for opportunism, for human respect.

Convinced Catholic and partner of the university Catholic youth of his city,

mistrusted the easy sneers of the sceptics, of the vernaculars, of the

mediocrity’s, participating in religious ceremonies, making processions to the

canopy of the Archbishop in solemn circumstances. When this and calm and fair

demonstration of his own belief and not an exhibition for other purposes, it is

beautiful and honourable. But how can we distinguish the "confession

" from the "affectation"? Here is life and the comparison of

words and of external actions that are worth little more than the words. That

young Catholic was indeed a believer. (...) Among hate, haughtiness and spirit

of dominion and of prey, this "Christian" that believes, and operates

as he believes, and speaks as he feels, and acts as he speaks, this

"intransigent" of his religion, is also a model that can teach something

to everybody. Perhaps Turati even suspected that the conclusive words used by

him to describe a convincing Christian secular ("He acts as he believes,

he speaks as he feels and acts as he speaks") these are about those that

the Church uses when it consecrates its ministers: a question of

"priesthood" in fact. And the Christian laic are also priests in the

power of the same baptism. There is another observation that is necessary to be

made before concluding. Often one hears a question (that burns above all the hearts of the Christians that live in

Piedmont): why is a land that was so rich of social " saints " up to

the end of the last century, today so dechristianize? What has happened? Where

is their inheritance was it not accepted and lived? Beatifying this last young

laic from Turin, the Church seems to give an answer: it needed (it needs) to be

welcomed this inheritance of Pier Giorgio Frassati (and today it could be” the

favourable moment").

The holiness of Pier Giorgio expresses in

fact a value of continuity with the tradition of his land and a value of

novelty: and this is his function of "zipper" (in the passage of an

age) that is necessary to know how to accept it. On one side he has inherited

the purest tradition of the Piedmont’s saints: he engaged in their immense work

of defence of the faith, through the profuse charity in the field of the

immarginalsation, produced at the time by a rising industrial-urban context. On

the other side, he has however pointed out the novelty: the necessity that faith

is compared in the arc of human experience and it "benevolently

operated" in every ambit: in the environments of the university, of work,

of the press (Pier Giorgio collected subscriptions not for his father’s daily

paper, but for the Catholic one), of political and party engagement, and

wherever it was necessary to defend social liberties, always trying to conceive

and to foment the associations, as " Christian friendship" destined

to the birth of a social Catholicism. While the age of the mass Christianisation

was opening and documenting itself, Pier Giorgio realised that it was necessary

to reopen the matter of the relationship of Faith-Operate: this was

traditionally applied to charity – assistance - moral fields, it was necessary

to extend it to all the operate of man (from economy to sport!), without

accepting limitations and pre-determined spaces.

This splendid confession of his remains:

Each day I understand what a grace it is to be Catholic Living without faith,

without a patrimony to be defended, without sustaining a struggle for the Truth

is not to live but to scrape a living... Also through every disenchantment, we

have to remember that we are the only ones that possess the truth. In an age of

sad dechristianisation, in an age of new and cheerful evangelisation we need

men like this: "convinced": laic, that is Christians: that means

saints.