INSTRUMENTUM MUSICÆ Which voice for Alfredo Piatti's cello? claudio ronco

«...And when that rending voice echoed, swollen with pathos, and unable, oppressed by desires, the nostalgia of obscure memories and boundless love, to say what it longed to say, - when that voice suddenly echoed amidst the hum of the orchestra, it was as though I could hear suddenly echoeing amidst the hum of a great city, the miraculous voice of a wild ass...»

Alberto Savinio, "The cello's voice", in: Scatola sonora, Einaudi editions.

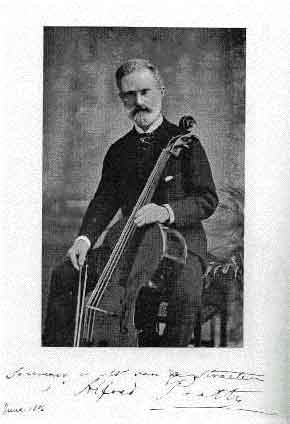

Alfredo Piatti

Please let me tell you a story.

There is a place in the old part of Genova, a street running between ancient walls, nearby Sant'Agostino, a few steps from an impressive group of concrete buildings, put up in the empty space left after an entire historical area had been torn down; that is where Nicolò Paganini's birthplace was, the spaces wherein he became a violinist, the place of the mystery of his genius. That is where old man Gaccetta lives and works, the carpenter whose shop lies under the Castello walls.

And Gaccetta is a small ancient man belonging to other times, his clothes that look like they have been copied from daguerrotype colors, with tufts of fine, ever so-white hair on his temples, his gaze always so sweet and far-off, his lively, affirmative, acute way of speaking. In his youth, he had given voice to that wood to which he devoted his life. Not because he was a violin maker, but because, fascinated one day by a street mandolin player, he had wished to study the violin and, miraculously, had become a virtuose. Then life was hard on him, and he had to give up studies and concerts, humbly devoting himself to voiceless doors, windows and wardrobes.

But music did not give him up, instead Giuseppe -Joseph, as he is named, as every carpenter worthy of being in a story should be- loves it like a sister, a mother, or a wife, and his thoughts and his nights are filled with music. Old man Gaccetta listens like no one can listen anymore: music nourishes him, rocks him, uplifts him to a heaven that we can only vaguely recall, where all things lose their weight and float, grateful to exist, in an absolute expectancy, without finality, without any other direction than that of gravitating around the invisible, ineffable center of musical enjoyment. For Giuseppe music is the supreme magic of paradox, whose reward is enjoying it above and beyond oneself.

This is how I met him: in his city, in the house of friends, the first days of this recording, when I played for them alone Alfredo Piatti's Second Sonata. Right before me, gathered in an armchair that was too big for him, Gaccetta could see my sound, my breathing. I could see his transparency, his lightness, nearly as if his body were nothing but air, even though it were as tense as a violin string. During the Adagio lento, Giuseppe's blissful gaze was engrossed by every resonance, and the notes I played could recognize one another in yet unknown harmonies, with miraculous astonishment they could see themselves reaching infinite distances, moving on the emotion of uniting, on the sorrow of parting, in dense remnants of memory, as though we had slipped into a hole in time, re-emerging ever so far from ours. And I didn't know whether it were in a past, or in a future. Without knowing how, I was one with Gaccetta -and his gaze, even if so intent in extreme far-offs, confirmed this with a certain grateful complicity- and as one we visited those so far away places, the harmonies of the spheres manifest, tangible, palpable, carrying our bodies, leading them through this giddiness, recomposing their fragmented perceptions towards such a sublime, elevated meaning of beauty.

After having already given me so much with his listening, Gaccetta wanted to present me with a gift, because he realised I was unable to come back to the time I belong to. Giuseppe took hold of my hands, telling me: «...there is a place, in the old part of Genova, the street below the Castello walls, a few steps from the house of that miraculous Paganini. If you know when to go, you can still hear the sounds of his violin... they're still there, suspended... waiting to be listened to. And you can hear them with your ears! Right there under the ancient wall, right by the theatre where he played, the great Nicolò, and Camillo Sivori, his only pupil, played too. There, where they learned Art...»

And I went there, on that night of January 8th, oddly warm and humid, like an Eastern night. I wandered alone, going up and down along that ancient rough-hewn stone wall, full of cracks and strange shadows. And at last I heard it. It caught me unawares, violently. A soprano sound, loud, tormenting, yearning, yet so very brief. I silently waiting for a sequel, anxiously holding my breath. Around me, the city, in its constant hum, a sonorous mist in which I sought feverishly to become compact, to uplift myself above its thickness to hear myself, to hear once again. And reached me once more: a panic sound, possessed, explosive in the viscous layer of the hum, electric hissing, remote televisions, far-off worldliness. Now it seemed I could recognize it, then struggling away, elusive, it slipped away, vanished. A sound of wind, and of membranes, fiendish, watery, and then angelic, cry, then song, sound of passionate love for life, and then burning tongue of fire, insistent, evasive, that make moods go mad. And then silence once more, bearing the painful longing to hear just one more time.

But, then, nothing. Nothingness and a visceral repulsion for reality, for time. My nothingness, and at last a "perhaps". Perhaps the wind, between the stones, the cracks and the shadows of the medieval wall. Perhaps just a south-east wind blowing, warm and humid like the one that softens the catgut strings of my instruments, makes them docile but untrustworthy, ready to betray me by whistling, getting away from the compass of my fingers and the square of my bow, to mock my striving to master them, to subject them to song. No, I know I heard Paganini's sounds: that sorrowful prison from which we can only escape by letting our fingers affected with tarantism dance and run, over the tightened strings, and the vibrating of woods, of air, of blood and flesh heal us for a while, until there is sound. Yes, not notes: sound. Breathing, moving wearily, or lightly, an unburdened spirit over and above the notes, beyond time.

***

Alberto Savinio compares the voice of the cello to that of the donkey. Or rather, he precises, to that of the «onager, the ancestor of the donkey». He says it «is a mammal which in its sound has something panic, something of natural sacrament and nowadays, since we're so unused to hearing it, something remote, unexpected, amazing...»

So now I could see where that sound was, and the wild sacrality of our musical rite, our repeated sacrifice on the altar of Iuval, of David, or of Dionysos. The noble calluses of our fingers, the adaptation of our body to the instrument, that slow Metamorphosis that turned us into Virtuoses, made us Works of Art: now I knew this. On a January night, in the old city pressed by the oppressive, cruel, arrogance of concrete, I felt as though the world had been freed from at least one weight: my own, that of my identity, of the ferocious crowding together of genes and intelligence, of individualities clamouring their immortality, or the vanity of having been. I would come back to my cello, to the microphones that gather and translate my sounds, to recording, to make known, or to exist, resist, repeat. Come back, just for the electric start signal of a recorder. And I knew that neither Paganini's sounds nor Piatti's, nor mine, could be found in those codes, those sinusoidal waves, those electronic multiplications of the musical body, nor would they have wanted to add themselves to the definitive, atrocious saturation of this round world, filling it to the last molecule with notes, annotations, comments, variations, old and new partitions to analyse, partitions already analysed, archives of a world of "too bad the world is like that and you cannot change it".

Or maybe you could. Perhaps the lesson of the Virtuose is but this: that becoming Work, or that parting with it, that cancelling oneself in performing it. Up to now I had believed I could clothe myself in my sound, disguise myself with my composer's music, invest myself as priest of the rite by repeating the visions, the visitations, the imitations of nature or of philosophy. And yet the lesson I understood now was the opposite of such vestment: it was the slow, gradual, solemn coming to music, like Marsyas flayed by Apollo and turned into a river, in dissolving into fragments of light and turning oneself into an Instrument:

Instrumentum Musicae.I went back to my cello out of the necessity of its voice. Oblivious of my fragile, corruptible matter, through layers of meaning, of all meaning, with the wonderment, the deep amazement of visiting the unutterable, being visited by it, suddenly, like a renewed memory, my playing the cello without using the metal end pin took on meaning, playing without that metallic resting on the ground, the reassuring fixedness to the center of gravity, useful and visible dispersion of the excesses of motion and vibration. Without the metal point, like those of old, like Alfredo Piatti -the last of the Ancients- I and the cello were two equal and symetrical bodies, and our body was the "form" of music. That is how we gave it to the microphones. That is how it is engraved in the numerial codes of this recording. But Piatti's sound is not to be sought in these notes. It is, as always, in the sublime remoteness of elsewhere.

Claudio Ronco, Venice, April 15, 1998;

translation by Susan Wise.

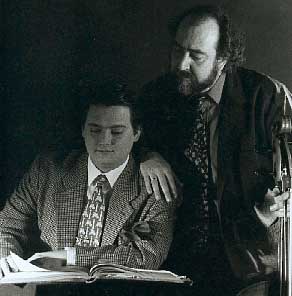

Claudio Ronco and Brenno Ambrosini,

the pianist of the first world recording

of Alfredo Piatti's Sonatas.

Alfredo Piatti, caricatura; London, ca. 1885.

other texts in English

claudio ronco