Itinerary of a recording

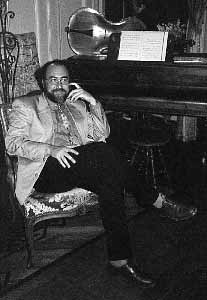

Claudio Ronco

Salvatore

Lanzetti, Napolitano,

Sonate op.I n. 5-6-7-8-9-11-12

Sonate op.I n. 5-6-7-8-9-11-12

Nuova Era Records, 1991.

cod 7048

Claudio Ronco

Stefano Veggetti

Diana Petech

Joachim Held

MP3 files

The man * The

interpretation * The

language * The Path

1- The man.

«...

despite its intimist, wise appearance this music may be placed

among the extreme arts: it gives expression to a singular, untimely

deviant even deranged subject, though with an ultimate touch

of sophistication it refuses the mask of madness.»

(Roland Barthes: Le Chant Romantique, in France Culture

(12/5/76).

There is little to be said about Salvatore Lanzetti

that is not to be found in any good dictionary of music: born

in Naples about 1710, died in Turin about 1780 (his real name

was Lancetti, but in the north of Italy everybody pronouced "violoncello"

with a z, "violonzello"). A pupil of the conservatory

of Santa Maria di Lorero in Naples, he was a cellist and composer,

active first in Lucca (where he played with F. M. Veracini) and

then at the court of Turin in 1727/28 and from 1760 until his

death. He was in London from 1739 to 1754 or '56 and also played

in Sicily, France and Germany. He is considered to be one of

the first great virtuoso cellists. He published at least six

collections of Sonatas for Cello and Basso Continuo (opus II,

howover, is nothing other than a re-working of opus I, transcribed

for the flute) and a method: Principes de l'application du

Violoncelle par tous les tons, which appeared in 1779 circa

in Amsterdam. Other Sonatas remained as manuscripts. Madame Marie

Thérèse Bouquet, musicologist at the Sorbonne,

very kindly offered me consolation when she confessed that she

could add next to nothing to the few details available about

this composer: at most she could add a few questions...

She did however point out to me the existence of two wills, drawn

up in 1750, separated by no more than a few months: the first

during a serious illness, and the second before Lanzetti left

on a journey to France, when he was completely restored to health.

From these two documents we learn that he possessed a considerable

fortune in shares, goods and property; he had a brother, Daniele,

a well-known theatrical agent in Italy (Vivaldi met him in Ferrara

in 1736), and another brother, Luigi, whose son Domenico was

an acclaimed cellist and composer. It is known that in 1737 he

married the sister of the Besozzi brothers (the famous Turin

oboists) but that in 1748 she filed for and obtained a divorce

on the grounds of torture ("sevizie"). I also know

that he was greatly appreciated in Turin, and in 1727 received

a salary of 1200 lire per annum (as much as a first violinist

and conductor), as well as a further 200 lire to provide himself

with an appartment. Lastly, it seems that he was the first

to perform a cello solo in the Concerts Spirituels in

Paris, on the 10th and 31st of May 1736, the year which saw the

publication of his first work: the Sonatas of our recording.

As I write there is nothing else to be added, except what may

be gleaned from a reading of his publication on the frontispiece

on which, under his name, he proudly states his origin: Salvatore

Lanzetti, Napolitano.

These Sonatas show us that Lanzetti was one of the first virtuoso

cellists to lead cello technique forward towards the conquest

of the most difficult uses of the bow (balzato ["leaping"

- the bow rebounding off the string], picchettato ["knocking"],

martellato ["hammered" - with a series of short sharp

blows upon the string] etc.), the performance of double-stopped

passages, of ingenious two-part patterns that call for bold,

complex fingering; and, above all, the mastery of the use of

the thumb as a "capotasto"', one of the most important

evolutions in string playing that permitted remarkable extension

of the cello's range as far as soprano high sharps.

His career may have been restricted by the limited interest that

the cello excited in his time: it was, after all, a "bass',

and the lower range indicated the plebeian, servant caste. The

idea of rising to the Olympus of the higher notes, of being a

"prince" or an "angel" for a few short passages,

did not, perhaps, even attract the curiosity of those who recognised

the sexual ambiguity of this type of instrument: "angelic

and sublime" (or morbid) like the song of the castrato.

The times were nor ripe: his patrons had not yet had the French

Revolution (at most they caught its scent in the air and were

worried), and perhaps Lanzetti, like a true Neapolitan -or as

we think all Neapolitans should be- aware of the necessity of

changing the tastes and prejudices of others, may have opposed

a noble, poetic indolence, or given himself over to melancholic,

perhaps sorrowing, disappointment. I know nothing more. All that

remains is a teaching method of no great interest, the few cello

Sonatas that I believe extraordinary, and a portrait in sanguine

which brings out all the pride of his "Neapolitanness",

where we see a man whose gaze is disillusioned, a little bitter

and ironic, but also extraordinarily mad, if indeed madness can

have been a part of his trade as Court Virtuoso Musician,

just like that provocative, exasperated "gesture" with

which he played the cello.

The

man * The language * The

Path

II- The interpretation

".. Interpretation

is seen here as the ability ro read the anagrammes of the text

(...), to draw out from the rhetoric of tone, rhythm and melody

the net of accents; and the accent is the truth of music, the

element that moves the interpretation."

(from R. Barthes, L'obvie et 1'obtus, Essais critiques III, Editions

du Seuil, Paris, 1982)

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the Sonata

invariably appears (with a few exceptions) as two parallel staves:

on the upper staff a melodic line furnished with practically

everything that the musician needs to know to perform it; and

on the lower staff a line of music generally lacking in indications

and suggestions about what is needed to accompany the upper line.

This accompaniment is more than one thing at the same time: the

"Basso continuo" contains, hidden in its melodic line,

a "fundamental bass", which one ought to recognise

at sight and be able to let the listener hear. The Continuo may

or may not have numbers written above the notes indicating the

harmony, but in any case only the bare minimum is indicated for

the performance of the Sonata - naturally with a great variety

of possible solutions - so that, in this part particularly, the

composer is inevitably held back from total possession of his

creation and from his own clear idea of what he wanted it to

be.

Opinions about how the Continuo should be performed are thus

controversial: is one to improvise on well-practised patterns

that are suited to the style and taste of the composer? Is one

to invent ex tempore musical sound qualities, situations and

developments? (In this context we should bear in mind the fact

that the Baroque Sonata was not generally written thinking of

eternity, but was expected to have a life cycle of a few seasons.)

Or again should one carefully arrange a well structured accompaniment,

perfect in every detail, so that every piece be offered a precise,

clear and invariable meaning? Probably all of these: I really

cannot believe that for two centuries performers refused to score

and prepare the Basso Continuo carefully; I am convinced on the

other hand that at times they developed it like a miniature orchestration,

just as certain keyboard accompaniments written by Bach, Handel

and others lead us to imagine.

In performing these Sonatas I have not aspired to so much, nor

would I have trusted in my ability to succeed within the time

limits of a recording: a Compact Disc today is little more than

an ephemera. Or rather: it is the great number of discs that

are produced that make it thus. Yet this music too deserves long

study, spread over the various experiences and mentalities of

music, just as has been done for those composers who have become

myths and models. Beethoven and Mozart have been performed and

studied incessantly: their "depth" derives in part

from this constant application. Purcell, Bach and Vivaldi had

to wait for generations to pass before musicians of a different

age recovered their work, and a couple of centuries before attempts

were made to reconstruct their authentic language faithfully.

For Lanzetti, I have been able to do no more than offer an earnest

performance, though one that had been pondered in only a few

months and realized in only a few days, for this first publication

of the work, in front of microphones that are much less attractive

than a real, live audience. I have, however, tried to orchestrate

the Basso using it as a potential orchestra, exploiting, that

is to say, all the combinations of sounds that I was capable

of imagining and producing. The choice of harpsichord and theorba

offers textures of timbre that are very different one from another?

Fine, they are used to highlight particular sections, or to emphasize

rhetorical solutions (for example the melancholy of a development

in minor) or again to isolate musical moments in which I am looking

for a special sense which I wish to render with greater clarity.

In any case the true Continuo instrument for these Sonatas is

the second cello: only this instrument is a true second voice,

or third, when the solo part duets with itself. I have asked

the second cello to perform the Basso, trying to follow me or

to contrast me, to join or separate itself from my musical discourse,

and also to harmonise as much as possible with double string

playing, as was the custom in Lanzetti's time. I have preferred

to score these parts rather than to have them improvised, for

they complement and enrich the double stopping of the solo voice,

and can share in its temerity as if there were an imitator of

Lanzetti himself playing the Basso.

In some instances I have chosen to have the second cello play

an octave lower, like a double bass (for example in the Allegro

of Sonata VI, where the instrument had to be tuned down a tone),

in other parts an octave higher (the parts written on the soprano

stuff in Sonata XII, and various passages in Sonata IX). I am

confident that these are not merely arbitrary decisions: they

should be contemplated among the many possibilities that the

extreme simplicity with which the Basso is written, leave to

the artistry of the performer. Scoring even a single double string

in a part that was destined for more than one instrument, would

have created confusion, as the addition of ligatures as bowing

and phrase marks would have confused the reading of the figured

bass. I could cite further little justifications based on practical

experience, but suffice it to say that I see the Basso Continuo

as a place where we should admit all the means and "artifices"

that we might plausibly presume were in use in the specific epoch

and school, and I mean by this everything that can be learnt

from the solo parts, even the most eccentric, of virtuoso performers.

Bearing this in mind I have accepted a copy of a theorba built

in the early seventeenth century, for the Sonatas of a hundred

years on, but I know that it was used thronghout the age of the

Basso Continuo, and perhaps only for this. The harpsichord

in this recording is a copy of a rather late Flemish instrument,

but is not unlike the instruments that Lanzetti would have found

at the time of these Sonatas; and then -forgive the brutality

of my confession- it was the only instrument available at the

time of our recording. The cellos, however, have been rigorously

restored to what we believe was their original condition, with

bows that are (correct) period copies, and gut strings with all

the ensuing qualities and problems. The pitch we have chosen

is 440, since this was most probably the pitch used in northern

Italy in the first half of the eighteenth century (circa 445);

the recording studio is modern, but has the same dimensions as

a baroque theatre; only two microphones, placed at a reasonable

distance, seemed to give a satisfactory reproduction of an ideal

listening position.

Lastly my approach to these pieces. I possess the Paris edition

which is undated, but is presumably the second, probably printed

by Le Clerc in 1738 or '39 (the first edition will have been

the 1736 Amsterdam version). This collection begins with four

short Sonatas, of medium or little difficulty (the level of difficulty

found in Vivaldi's or Marcello's Sonatas), fairly conventional,

but quite charming (especially Sonata III, with its delightful

Minuet). From the fifth onward the Sonatas become dramatic compositions,

and are rich and virtuoso, as if the first pieces were intended

for amateurs, and the others for professionals (understandably:

at the time there were more amateurs than professionals among

the purchasers of musical publications). Two Sonatas, number

eight and number ten, were certainly intended for a five-string

cello; despite this fact I have performed number eight on the

usual four-string instrument (and number ten is not included

in the CD ). In the other Sonatas even the frequent sharp passages

are conceived for a normal cello, with advanced use of the capotasto

thumb, indispensable even if they are performed on a five-string

cello. The style follows a formula that was quite common at the

time: a mixture of French and Italian taste, but with several

moments (e.g. the Adagio in Sonata VIII) which sound as though

they were written in the years of Boccherini and Haydn (or in

imitation of certain German music like C.P.E. Bach): the galant

gesture, the "lightness" of the phrases, their linearity

seem already "classic", but their are no doubts about

the dating of the works. Elsewhere the scoring is bizarre in

the asymmetry of its rhythms (Minuetto of Sonata V; central development

section of the Largo of VI) or in the frequent interruption of

melodies with pauses, or with arpeggio chords, whose execution

is not clarified.

Ritornellos are present in less than half of the pieces, though

never in slow or cantabile movements. The Adagios, Andantes and

Largos, in fact, follow emotive directions that are clearly evidenced

in the scoring and in the invention of the phrases: I do not

think they would tolerate any repetition not founded in their

poetical design. Nor would there be any scope - either in the

Adagios or in the Allegros - for inserting ritornellos with significant

diminutions or embellishments: I believe that Lanzetti left this

sort of thing to Corelli's music, and that his idea of composing

was quite different from all this. He writes, naturally enough,

as a cello virtuoso; such that all his ideas seem to spring from

his instrument; I imagine, therefore, that he must have taken

delight in attributing precise values to certain sounds in certain

positions on the fingerboard; for example: the central B flat

on the first string (a slightly unnatural note, since the hand

of the baroque player is habitually looking for the A that precedes

it) is a note which recors invariably in almost all the movements

of his Sonatas, always tending to generate tension, dramatic

stress, both when it is to be "shouted" and when it

is to be "whispered"

Again, in the numerous passages for two voices in the solo part,

a note is often doubled by the Basso. One would almost like to

have it played by the other instrument, so as to avoid the risk

of producing unpleasant unisons if not perfectly in tune. Yet

(playing them in tune) the effect is marvellous, thanks to a

well-hidden virtuosity. The truth is that the greatest difficulties

in Lanzetti seem to hide from superficial ears, rather than shining

out in "special effects"; it is a good sign, but not

for Lanzetti, who lived in an age that too often was superficial,

at least as far as music was concerned.

Indeed, it was by playing this music, rather than by reading

it, that I perceived its nature: it is music made of gestures,

movements of the body, pulsations, calm or troubled breaths,

of the desire to "be" and to "speak". It

is dance, song, vision, everything that a body can create. This

is why I gave up looking for the "logical sense" in

the phrases of its structural development, in their rhetorical

valency, in the mesh of agogic accents, and I sought out only

the value of my gestures in the act of performing the written

notes: there I found that real, living «body», that

moves in a manner perfectly coherent with its nature, pronouncing

phrases and fragments of great poetry. I looked for the "actions"

of that body that lie hidden behind the codes of its written

form, within the weave of its accents, all those dense, strong

sounds, charged with "intentions", that generate movement.

To all these I dedicated my capacity for concentration, my emotivity,

my desire to express something that was born within me. And I

believe I have interpreted Lanzetti.

the

man * The interpretation * The

Path

III. The language

" .. for

if only you wish to move back a little to its (music's) origin,

you will find a living, enduring, inexhaustible source of philosophical

cognitions that are not common." (Decio Agostino Trento:

preface to "Trattato di Musica..." by G. Tartini,

Padua, 1754).

Perhaps I am incapable of seeking, in the arts,

anything other than the signs of unrest. Perhaps because those

signs stir my desire for art, or perhaps they are simply elementary,

universal signs of an attention that moves towards the unconscious,

like the act of listening which is directed automatically towards

the content and meaning of a discourse and then, at other times,

only to the abstract sound of the voice, with its unending chain

of significances.

When we attempt to find these signs of unrest, no historical

period is better or worse than another: the most bewigged baroque

will do quite as well as the most tormented romanticism. For

-as we know- a work of art is similar to the human being who

observes it: body and soul, the conscious and the unconscious;

subject to the time in which it articulates its own existence:

changing, communicating, expressing meaning; in short: living

and summing experiences.

In music, the experience of listening may follow a linear progression

in time as in narration, where the present is variously charged

with the past and the future, but is proceeding towards a specific

end (and this is its manner from the ideation of Sonata Form,

throughout the entire Romantic period); or again it may develop

in a "circular" time ideally unmoving, where a supreme

synthesis of things is offered in apparent immobility, -whose

symbol, or artifice, is cyclic action- similar to that of an

allegorical statue absorbed in the timelessness of its messages.

In the latter case it is only the individual observer that can

make it dynamic, translating it in his own intellectual and emotional

activity. Thus it is -in varying degrees- in every art form;

or at least it seams to me that only thus can its decodification

and fruition be commenced: from the abstract to the concrete,

or vice versa, producing those results that our culture and sensibility

can achieve. Such then is music too: ineffable in its extreme

abstraction, in the fact that it shares in the idea of a space-time

collocation that is peculiar to the gods and not to mortals,

or concrete, "physical" in that it is similar to a

pulsating, rejoicing, suffering body.

Music too eventually treads the path that leads to the opposite

of its initial condition: in the absence of a "tale"

structured in time and in the "material" of humanity

(a Bach Fugue, for example), there emerges an inner plot, a "voyage",

an approach to emotive events that have something to say. When

the music develops situations that can be identified (it

is "descriptive" by means of rhetorical effect: associations

{horns/hunting] become allusions or metaphors;

similarities [violin tremolo/shudder, bass tremolo/terror] are

cases of paronomasia..., all in all chaotic, uncontrollable chains

of potential equivalencies - or of figures in which we can read

more than one meaning, held in control only by the music's general

rhetorical structure or by a title) or that can be derived directly

from a concrete reality (such as certain guttural sounds produced

by the jazz saxophonist, which move their listener violently,

since he can feel the sound vibrating in his own throat), we

may find ourselves roaming in the natural abstraction of "narrating" in music, towards a pure, absolutely free form of wandering;

in Vivaldi just as in Shostakovich. This because -though the

fact is not widely known- the work of art is similar to the search

of the artist, to his awareness (or lack of awareness) of the

fact that Art is first and foremost the act of seeking,

of awaiting the ideal or perfect artistic event.

When I study the shifts and paths of musical language through

the centuries, I have the impression that I am awaiting something;

the fragments that I seem to find are always stimulating, for

in a sense they belong to me intensely; all of this whispers

a simple secret to me: everything is within me, and is susceptible

of decodification, like a microcosm. I must recognise my language

as being similar to those steps forward and digressions found

in history, for I too am "structured" in that manner:

it is the result of the regular sedimentation, of the constant

overlapping of events and experiences in the history of our civilisation;

each of these still belongs to us and is a part of a whole, that

is at one and the same time, chaotic and organised; every fragment

may be isolated here, but may continue to act within the whole,

without being consumed. Every history -collective or personal-

is "transparent" in its overlapping with another. Observing

the "metamorphoses" of a Vivaldi into a Beethoven,

then is really the same as looking at oneself in a mirror (with

all of the vanity that this entails).

And Lanzetti? Lanzetti is a character of his time -of History,

irretrievable in his totality- but also of my time, as long as

the "mask" I don to perform his work (authentic instruments,

authentic language) does not annul me as an individual. A mask

may not be transparent (it would be annulled even in its ritual

value), it can nonetheless generate new codes, which when they

are decodified, do not lead us back to a world, an "external"

place, be it historical or symbolical, but to an "interiority",

where every meaning is possible: the Theatre which shifts its

focus from the mythological individual, to the "concrete" individual in his totality.

Lanzetti is indeed a theatrical narrating musician. He has his

tale proceed in a time that is marked out by the perception of

life, and that is consistent with the rationality of the body

and the irrationality of the soul or the mind. His music is dionysiac

(from man towards god) not apollonian (from god towards man):

it calls out in the listener a panic in the Greck sense: the

anxiety, the uncertain fear that the Ancients attributed to the

presence in nature of the god Pan. It seems to seek expression

in an almost literary form, developing and arranging ideas that

resemble complex rhetorical figures (one example may suffice:

Antanaclasis or Reflexio: we encounter this figure

a number of times, but we need only listen to it in the Adagio

Cantabile of Sonata V: a brief, concise musical phrase is expressed,

and then disappears. It emerges again at the end of other phrases

which develop their own, separate discourse. As it reemerges,

its "sense" is perceptibly altered, and the listener

wanders: what does it mean? what is happening? why does it return

and express things which seem to be so different?). I really

cannot say how well schooled Lanzetti was; studying was no easy

matter in those days, but music was in great demand, and so much

work was done and much repetition was used: this means

that many "cultured" aspects of his music may well

be there quite by chance, or rather by virtue of an excellent

instinct for imitation. Yet I would like to think that his choices

(even if unconscious) were horn of a desire to narrate in tragic

fashion through the ambiguity of his manner (Italian/French,

galant/restless, playful/tragic) in an attempt to counter those

who made music only for pleasure: to entertain. To seek

out then, and to choose that which would be the "crisis"

in the romantic sense of the word; what the painter Füssli

would describe in a splendid aphorism some decades later as "the

central moment, the moment of expectation, the crisis; this is

the moment that counts, full of the past, charged with future...".

If so it was, then this is why Lanzetti wrote for his own hands

and arms that could play the cello: body and soul closely bound

together, seem suspended in that absolute expectation that is

the unique and inappellable condition of being human. This is

the twin reality of the mystic; he desires nothing more.

Lanzetti is indeed a Virtuoso of the eighteenth century, whose

profession causes him to seek to render natural to himself what

must sound transcendental to his audience. Clearly his work may

not be too unlike the work that his century imposes, and to communicate

his language must resemble the rhetoric that is in currency.

His way of being a cellist is then simply derived from the fact

that he plays the cello in those years: he accompanies instruments

and voices in the theatre or in Chambers; he follows,

flatters and converses with the soloist; he represents scene

setting, space and measure for the singer who is executing the

Recitative or the Chamber Aria with Continuo. He may duet with

the bass and tenor voices, even with the Sopranos: he is capable

of becoming their substitute, and inevitably he will eventually

appreciate the immense expressive strength, that lies hidden

in the "substitution" of a voice made of bone, cartilage,

muscle, gut, humour and tissue -all in vibration, all sharing

in a sound which is heard in its entirety by other similar

bodies- with the voice of a vaguely anthropomorphic instrument,

if the latter is handled with skill. The body recognises the

sense of its own sounds, and on this occasion the game of substitutions

has tremendous potential, for, as Barthes puts it: "if sensible

phenomena do possess a meaning, it is always to be found in movement,

in substitution; in short: in an absence which is more clearly

seen" (op. cit.). This then produces an unending chain of

other meanings, which a man of the theatre, with his intuition

and experience, can easily recognise and exploit. It is evident

then, that the virtuoso instrumentalist will in the end create

music on his own sound and personality, and thus will compose

things that resemble his own mental and physical persona:

selfportraits (once again, the element of vanity...).

Thus if Lanzetti's cello "sings", it is not merely

because it has singing as a model, but is principally because,

having been brought up among the finest theatrical singers, like

these singers it does not articulate sounds in musical

phrases, but pronounces a text, founded on sounds; in

other words, his cello "speaks". And it speaks because,

in a sense, it has become a living, throbbing body, complete

with an "idiom" of its own with which it can express

itself: its style, that is to say. This cello and the music written

for it, through a rhetorical language which is still perfectly

effective, enter into a parallel "world", which has

its own Nature and Culture, sure that their messages can be decodified,

since they are expressed in a similar, though metaphysical,

reality.

The ear tries to catch "signs": "I listen as I

read, that is to say, on the basis of certain codes", Barthes

remarks. Thus it is that if Lanzetti's cello "speaks"

to tell its tale, then his music too -his "tale"- becomes

a body, which moves, acts, listens and moves on gathering experiences.

While all this is going on, we perceive its truth, for everything

can be recognised in the authentic onward motion of life, that

can be identified in its natural directions. Thus it is moreover,

that the performing artist must offer himself alone as an individual

being: authentic, unique, perfectly human: not sublime or divine.

The person who performs guides the person who listens by means

of his own experience of the things that belong to a shared reality,

as in hyper realist theatre: "love with me, for I love.

Share in my suffering, for I suffer", he might say.

I attempt to "pronounce" every phrase that I play,

I try to imagine the sound as a "body" that bends,

stretches, leaps, contracts, speaks; for -as lovers of Dance

will understand- in a manner that I feel intensely and that fascinates

me, every movement of the body is immediately "translated" into movement of the soul.

The

man * The interpretation * The

language *

IV- The Path

"The unconscious,

structured as a language, is the object of a particular and exemplary

way of listening: the way of the psychoanalyst." (R. Barthes;

op. cit.)

I have reflected at length over the decision to

publish the following (many are irritated by the notion of reading

music through images, and would like to feal free of it), but

even the God of the Bible, immaterial and without form as he

is, needs to use hands, eyes, ears to be understood and followed...

and then, more than anything else this is my personal, interior,

almost secret path, often hidden behind a performance that is

apparently less dramatic; but these are the ideas I used to make

the musicians who accompanied me understand me, and thanks to

these "tracks" we shared in a musical experience. I

shall publish then, and if I am wrong to do so, I shall take

the blame.

Greek vocabulary is a useful aid in ordering the succession of

events during the performance on this disc (this too is a suggestion

of Barthes). There is a fact, pragma; a chance occurrence,

tyche; a solution, telos; a surprise, apodeston;

an action, drama. Everything comes about as if we were

in the theatre: we take the disc, insert it into the player,

sit in front of the loudspeakers, the curtain rises: we follow

the events, receive the messages; when it has finished, we feel

that something has happened within us. The pragma, the

fact, is I playing my cello, my colleagues, their instruments.

The tyche, the chance occurrence, is the manner in which

the interpretation of the Sonatas begins to uncover directions,

correlations, "signals" of meaning: the baroque Sonata

is aleatory enough to turn even into the opposite of what one

intended to propose. It is with a great deal of chance that I

find suggestions on how to direct musical events; seeking them

in rational ways might be merely deception. The telos,

the solution, comes about by necessity: in this, musical ideas

find their concrete form a finality: what I hear now has a more

precise sense, for to give it a sense, now, is no longer a desire:

it is a necessity; I cannot accept the abstract, if I have not

attained it through the concrete. The apodeston, the surprise,

is the destabilising event, the first to generate the "crisis",

to drive me violently towards action; but it also resembles the

re-awakening of the consciousness, the exciting revelation: it

is unfurled, and opens out new horizons; the desire is:

to go on, to become involved in the facts, to act. The drama

the action, can now be experienced wholly, accepted without restrictions,

shared in the first person. The first rule in music is, perhaps,

to excite in the listener the "desire" for music, and

perhaps this very desire is the "action". All

of this happens in any case, both in the act of playing and in

the Sonata itself. What follows then, is the path I have taken

through the seven Sonatas on this disc.

The rhythm of baroque music contains something urgent, unrelenting,

as though it were trying to represent the time to which

every living being is subject. In short, if music is rhythm and

melody, then the melody is the soul: free, potentially unconditioned,

but temporarily bound to a body, of its own nature a prisoner

of time: the rhythm. The Baroque might never tire of playing

with this idea, ordering it in varying manners in rhetorical

figures: Allegory, Simile, Comparison, Metaphor Thus rhythm -or

the absence of rhythm- becomes the fundamental element

of the music (whereas in romanticism the "body" might

also be the melody: the theme). And in the Adagio Cantabile

of Sonata V we do indeed begin without a real rhythm: two pauses

written on the bass line dissolve its initial rhythmic sketch

into nothingness. It is as though it had no body but ouly a "desire"

for a body: I have no form yet, I am only an idea: I rise

up in search of a heaven, and the Basso calls me back -rhythmically-

to earth.

After the second pause sign, there are four trills, like nervous

shudders: I feel as though I were shaking off my torpor: now

I have a body, and I enter the rhythmic "machine" with

energy. With anger too: here is the first of the high B flats,

which I must play as though suffocating a scream in my throat;

immediately after this, I walk almost in pain, my head is bent:

now I have a body, and it moves through the fatigue and suffering

of living; it moves on, accepting and rejecting, stopping and

then running. It discovers that it is proud and desirous of love,

of kindness. It lets itself be drawn along (with ouly a minimal

attempt at holding itself back) by a movement from the Basso,

a movement that is majestic, impetuous, emphatic. It cedes again,

picks itself up again, walks on in pain, its head bent; it rebels,

and once again the pauses reappear: two, as before, but now that

body exists, and I cannot but accept it.

There is a pause: a silence which sounds alarmed to me; then

I read: "Volti" [turn the page] (in other places

I find "Segue" [next section follows without

a break] or "Volti subito" [turn the page quickly])

and I continue. I realise that it is the marked strict rhythm

that is disturbing, and that it is the pivot on which rests the

entire dramatic effectiveness of the piece. The Allegro brings

it back in the same function, but at first it seems to be clearly

separated from the preceding movement, and it is here that I

detect the first truly significant signal of Lanzetti's restlessness:

it begins like a brilliant, virtuoso movement; throughout the

first part it develops like a light comedy: a charming dialogue

between lovers, a succession of sparkling and sweet incitements;

then, in the second part, it becomes tormented: the same incipit,

now in C major (a third higher and thus more emphatic; in rhetoric

hyperbole) becomes aggressive, agitated. All the phrases

become painful or more perturbed; trills repeated on the same

note come back again. Tricks of the bow which, at the beginning,

were joyful acrobatics, are now performed on the outer strings,

with anger, effort; everything seems to be exasperated and seems

not to reach any conclusion: only the return of the initial key

with a phrase of convenience, to annul, to cancel a discourse

that was becoming intolerably serious. It is as though it finished

in nothingness, in emptiness: there is an ellipsis of thought

(reticence, aposiopesis) and we feel it quite clearly:

silence dictated by modesty. At this point the score calls for

the Ritornello of the second half too, but I could never

repeat it; I am convinced that it is there only as a sign of

respect to symmetry, but nobody would want it. In this non-conclusion

I am left dangling on a thread: I can only fall straight down

into the Minuet. It seems to begin from nothing, or to

have come out of another silence; I want the two cellos alone,

for all the first part. The harpsichord enters in the major,

to confirm its joyful colour A little later I play a duet

alone, with the Basso gracefully chasing after me. In the Da

Capo everything seems to fall into its rightful place: a

galant Sonata, in elegant livery, for a high society audience,

well served and entertained.

The sixth Sonata seems galant too, when I begin the Allegro.

Galant and calm, like a walk in a park amidst calm, smiling middle-class

strollers. It calls to my mind pieces of celebratory music by

Elgar: "unproblematic", self-assured, with a clear

conscience.

I move amids fond phrases: the music I play reassures me, pleases

me, tells of pleasures. But immediately the following Largo is

an intensely melancholic melody; it proceeds a while, then it

is suspended a moment (there is a pause marked), and suddenly

it is replaced by a totally different figure: a chromatic descent,

dancing on regular, dotted quadruplets, light -calling to my

mind a coach driving along calmly- yet full of subtle agitation:

undefinable, somewhere between a sense of weariness, of disillusionment,

and a gesture of extreme emotion, almost of sorrow. It finishes,

and the melancholy theme returns; now it is tormented: it writhes,

it seems to have no end, but it lives in its own sublime sensuality.

I should never want to leave it: to forget my destination. Another

pause, and the coach rolls on again, with a rhythm like an obsession,

a trance. Have I been riding in the coach all the time?

Dreaming at times, and moving away from the place where she whom

I love was present, she who made my life pleasing by being at

my side? A pause mark suitable for a cadenza brings these questions

to mind, just before the last note of the Largo.

The harmonic path of the Sonata is simple and effective: B flat

major the first movement, and G minor the Largo, which closes

on its dominant, very gentle in concluding the final movement

with a return to B flat; Lanzetti uses this pattern almost always.

The finale is a Gavotte with six variations: here, on

an elementary Basso, always repeated in the same form, I decide

to play on an obsession: in these variations I can find nothing

other than bitterness, and I accept it as it is: an obsession,

or at most a monologue on an obsession (how indeed could it be

a dialogue, if the journey has led me away from my beloved?)

I reach the conclusion without having shaken off my obsession:

I shall continue to hold it within myself: obsessionately.

Sonata VII also begins with a galant movement (it is rhetorical:

it is called Captatio Benevolentiæ...); it is rich

in ideas, surprises, brilliant and curious gestures. Yet it has

no conclusion: it flows (or is transformed) into an impassioned

fugato: as I play it, I feel as though I were being sucked

into the whirl of a frenzied dance. Halfway through it suddenly

changes: out of nothing there emerges the minor key, with

a phrase that sounds like a tongue-twister in Neapolitan sorcery

(this is why I play it with "notes inegales":

not to make it French, but to produce that effect of popular

music, that certain "swing" that is a little magic

and a little primitive), then it takes on darker shades, like

a Sabbah painted by Salvatore Rosa, and the return to

the major key is only a reversal of the lights: nothing could

stop the rush of notes: I cannot yield, or hold back, except

in a chord that once again is suspended in emptiness: before

me, the Largo in E minor and the inertia of the "fuga"

squeezing me from behind. Here there is a long note, while the

Basso begins a regular, slow, expanding movement; then a trill

(it must gradually increase in tension: carry the voice),

then a melody, that is so intense, so impassioned that it must

be shouted with one's whole body, until blood pulses with the

pulsing of the Basso (the dynamic mark is Forte: it is

to be taken literally: with physical strength). Then straightaway

it is all interrupted: we read: "piano, Arpeggiato",

and the same sequence of pulse beats is repeated in emptiness,

in the desert, in the startling absence of the melody. The first

time I played it, I felt a sense of bewilderment, then I came

to love that absence better than any reappearance of the melody,

splendid though it is; when it disappears it seems to be all

the more present, and its secret charms me. Is this a dialogue

with nothingness? Or is it an deliberate conscious act of substituting

presences with absences, to rise still higher,

to touch with one's hand an abstraction that is even more sublime

than music itself? The trace -the artifice of that void-

gradually loses effect as the Largo proceeds, and it too becomes

present, concrete, sentimental. It is with this shifting element

(at the beginning it is the Basso line, then it becomes the absence

of a melody, lastly it is played by the solo cello, in two parts)

that we reach the conclusion: a pause of great intensity. After

this I would have the Rondò explode, and it is

an almost satanic Rondò: here we have the trance, the

obsessive beat of primitive dance: it has no beginning and no

end: I listen to only a fragment: it has been and continues to

be. It is a dance that is as old as man: it represents the eternity

of the gods. Yet is it also nearly a revelation of what the fugato

-behind the apparent austerity of its form- was hiding: the magic

of its own origins?

Sonata VIII is a subtle game: its is suspended on the delicate

thread of the bow stroke in the rapid triplets, in seeming contrast

with the indication Allegretto, considering the calm pulsation

of the harmonies and musical ideas. In fact, there is something

serene about the latter, something agitated about the former:

an agitation which, while it may be joyful excitement (Nature

as friend expectation of the beloved) is also a subtle form of

uneasiness (Indian music has a very similar Raga: Lalit;

imagine a prince at dawn on the day of his wedding). The second

movement is an Adagio; majestic at the beginning (triumphant

entrance of celebrating Nymphs?) and tender and loving in its

development. I chose to perform it like a love duet with the

harpsichord. It seems to me to be like a dialogue of tender,

sensual gestures; the harpsichord manages to find something feminine,

innocent, silvery. Those long syncopations with their sweet embellished

resolutions are like long lovers' embraces. And in the Allegro

finale the agitation returns, only this time a little more

dramatic: it is torment, excitement: it is the desolation and

desperation of the abandoned lover. I have tried to find other

things in it, but have been obliged to yield to this violent

anticlimax.

I find this desolation and desperation again in the Sonata IX:

a heavy sensation of pain and weariness. It seems to be a part

of the Adagio, raising it to the point of tears, to a

scream of anguish. I proceed in the Allegro with something

like the rage of one who is trying to drive out the demon of

torment: trying, even weeping over myself to relieve the pain,

but finishing by screaming it out aloud, abandoning myself to

lamentation. Paradoxically, this act of screaming out against

the fear of death is a shout of life, and in it we may recognise

all human dignity. It seems to find no path to follow: only broken,

acephalous sentences, like funeral columns. To conclude, Lanzetti

here writes a very brief, stylised phrase, so strongly contrasting

with everything that has gone before, that it sounds sarcastic

(I have toned it down by playing it twice, for I could not bear

its brevity; but in rhetoric this is Antiphrasis: it means

the opposite of what it affirms) I perceive the probable reason

for this choice: a clear sharp cut is needed to end this movement,

and this calls for a language that is quite different:

the actor has let himself go too far, he has become a real man,

has really soffered; now he is an actor again; he takes his bow,

and the scene changes. It is a Rondò full of sweet

melancholy, agitated to the point of madness. At the point in

which the cello voice is to rise up to the high sharps, I wanted

to have the harpsichord play alone an octave higher: I felt that

in this way I could make the musical effect less ferocious, though

I have repented a little: when I left the Basso "a loco"

and the second cello played too, the impression of solitude in

my part was harrowing; but I found it excessive.

Then, tenderly comes the Da Capo. If one has to repeat

the beginning of the Rondò, then one might as well recuperate

a sense of serenity and peace in it (although, if this contains

a rhetoric figure, it is Dubitatio: let the audience choose

the sense of this finale).

The opening of the Sonata XI sounds like a bold, clear, sonorous

symphony. It seems to imitate the interplay of solo and tutti

of a chamber orchestra. The development is lively and serene,

rather like in Sonata VI. Once again such a reassuring, even

conventional movement goes on to startle the listener: a bizarre,

brief, intense Adagio, fragmentized by arpeggio chords,

repeated in Forte, pauses and highly contrasting dynamics.

I decided to render it similar to an almost recitative,

underlining this idea with brief cadenzas on the three pause

signs. This "reciting" led me to a profound, insuperable,

even violent sense of solitude. The final phrase of the Adagio

closes in a penetrating, intense pathetic suspension, and the

cello solo begins piano an Allegro fugato that

is quite different from the one in Sonata VII. The melody that

I have to play here mezza voce, sounds infinitely sweet

and full of sadness: now I think that my intuition was correct:

there is a great sense of solitude. Here again I want the two

cellos: alone. I ask the two other instruments to wait for the

return of the theme before playing together with us. Then everything

passes into another Adagio, very short this time: it seems only

to wish to repeat the finale of the preceding Adagio (it

is almost the same melody), in search of a new development. This

time it develops into a Rondò, almost grotesque in the

way it becomes heavier and tries to be majestic. Convention would

have it repeated after every variation, but in this instance

I do not think this is what Lanzetti wanted: the variations are

written out in succession, and only at the end do we read "Segue

il primo Rondò sino al segno" [repeat the first

Rondò as far as the sign]. The justification may be weak,

but all the variations seem to come from a "world"

that is quite different from the first Rondò, and to be

seeking each other in turn. Thus, amid languid, drunken affections

with the sweet rhythm of the melody (it sounds more like a Sicilienne

than a Rondò) we reach the minor key: and it is the most

pathetic, the most heart-rending, the bitterest that I imagine

could be written for the cello. The return to the first - massive,

heavy, almost clumsy- Rondò is of so little importance

that I discover that I still hold within myself all the feelings

that came before it, all still intact: the finale closes

like a coffer made of iron and solid wood, full of precious things.

Sonata XII opens with triumphant fanfares: the key of D major

helps: it is sonorous and vital as no other key on the cello.

A bold festive phrase (I have been told that it is the same as

one in a cello concerto by Boismortier; who knows who copied?...),

played in unison, renders the idea of an orchestra, and the soloist

plays above it with splendid virtuosity, amidst flashes of light.

This is the Sonata that makes most use of the soprano voice,

in brilliant, ingenious manner, played with humour, charm and

taste. Everything is concluded without a change of tone and without

excessive severity, sounding like the Sinfonia before the curtain

is raised. Indeed, I am certain that this was its intention,

for the Andante cantabile tbat follows really does sound

like a pastoral scene. It is so full of descriptive elements,

all set out in order and clear in their rhetorical meanings,

that I cannot help yielding to the temptation of portraying it

like a painting: set between two large, leafy trees, close by

an amenable hedge, two young lovers; she seems to abandon herself

on the grass, inviting love; he reaches his hand out to her,

as though yielding to her desire, but his gaze is directed towards

the background. Here we see a distant valley, through which flows

a sinuous river. On one side two horn players raise their instruments,

while two deer run away in fright; they are followed by a pack

of fierce dogs and hunters on horseback. Now I no longer know

if he, the lover, asks her to get up and watch the fate of the

deer (with sadness? Lovers think of death with scorn), or if

she asks him not to look, to forget the struggles of life and

abandon himself to the carefree joys of love. As I play, I seem

to hear the horns calling the dogs running, the deer trying to

get away, their fall overwhelmed by the noises of satisfaction

and victory. I seam to see the lover get up or bend down, calling

or being called by the sweet sensuality of the woman. Everything

is motionless, yet alive, dynamic in the secrets of its allegories.

There now follows the most amorous Minuet in the entire collection

of Sonatas: full of a light that is so serene and pleasant that

I could not do other than orchestrate it for all our instruments.

Each has his turn and plays with his own loving phrases, as fair

as the harmony of life that music delights in imitating. Or,

perhaps, as fair as madnes, for, as Barthes remarks: "the

musician is always mad, unlike the writer, who may never be mad,

for he is condemned to meaning".

Post scriptum

All the work

on this disc was born and grew out of a reading of Barthes. It

was therefore inevitable that this should have flowed into this

text, even though mainly unconsciously. Where Barthes is quoted,

he is quoted in a sense that is quite unfaithful to the original

meaning, in a transverse reading that he would surely have appreciated.

I hope my readers will also have appreciated it.

Claudio Ronco,

Venice, july 1990.

(English translation by Timothy

Alan Shaw)

back to the top * The interpretation

* The language * The

Path