AN INTERPRETATIVE ITINERARY

AN INTERPRETATIVE ITINERARY

«Beyond narration and description, music which evokes the voice attempts to reveal a mystery: the mystery of its origin.»

Danielle Cohen Lévinas, "La voix au delà du chant", Paris, 1987.

Allow me to be your guide: put on the Larghetto con moto from Gade's "Novelletten"- the fourth track on this disc - and let the first two chords of the piano serve as an invitation to enter the visions of an improvised poem:

Night falls on their sleeping forms,

Caressed by the gentle breeze

Beneath the moon they are faery dolls who dream of love;

While all about them, the lake trembles

With a rythm moved by my heart-beat,

Rippling toward the quiet features of their faces.Try to imagine that only the piano accompanies and sustains you in this dream: dissolve the violin and the cello; let nothing of them remain but caress, desire, a light body which moves, vibrates on your breath. If you succeed, if you can evoke the vision of a lake by moonlight in which the sleeping face of a doll floats like an island, or if some other itinerary of your own, dreamlike, different, or inexpressible, possesses you, then the effort-of making this disc, of conceiving and writing a poem for each of these compositions, of believing passionately that the Danish Romantic composers should receive more attention from all of us who interpret and benefit from their art - will have been worth it.

Do you find this music similar to Schumann's? Nothing could be more natural: they came from the same school, they were friends. But no one finds that Hans Christian Andersen resembles the brothers Grimm: they merely pursued the same career, lived in cold climates, and had a similar cultural heritage. In literature or in painting, however, the differences are sometimes easier to detect. In music we depend on something much more intangible than words or color: we come into the ineffable. What takes over is the unconscious, or better, the unknown, which we too often try to avoid by keeping a sound or a phrase within the limits of the known, of the familiar. But it is thus that Gade resembles Schumann, and Schumann runs the risk of resembling only himself, without encompassing anything beyond what we already know about him. And music must be the uninterrupted exploration of the unknown, it must perennially renew itself in a listening which is creative, dedicated, and loving.

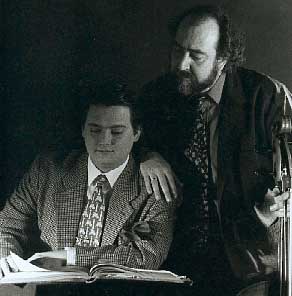

I invite you to return next to the beginning of the disc, and to let the five notes repeated by our instruments become the excited pounding of the pulse, our own excitement in preparing to listen to a story teller who will now tell five "Novelletten" (little stories). And just look at his photo.

Doesn't he seem-with that book laid across his lap, that wise and peaceful gaze-the narrator who has just finished reading his story to us, and now, satisfied, accepts our appreciative gaze like a benediction? Note carefully: the cello and the violin are the voices of a man and a woman, and togheter with the piano they make a "voice" out of the hammered string, or abandon their single corporealities in blending or hiding within the resonances of the pianist's chord or arpeggio. Inevitably, writing for a piano trio creates an happening, as between two lovers, where there is a third presence - distributed variously among the three instruments - which is "locus," or soul, or vision.

Move then to the sixth track, the beginning of the great Trio op. 42: the piano presents a theme which sounds like an exhortation, a request for something, and introduces a strand of great disquiet, whose cause seems to be the movement of the two bows in a synchrony which is, by all means, structural -harmonic, contrapuntal- but which seems to be located on two levels in two different and non-communicating "realities". If we can imagine that they resemble the tragic desire of a man or woman who wants to regain a lost lover - like the musician Orpheus who tries to bring Eurydice back from the dead - then the last phrase of the first movement, which on paper seems so trite, leaden, and impoverished, will not leave us imagining the author as incapable of good musical inventions or of grand rhetorical gestures. It will rather seem to us like the moment in which the true poet, strong with the truth of his inspiration, describes for us the thrill of reuniting the two who have been separated by life and by death, in the very instant that they attain a physical contact denied by fate. Through the power of music the violin and cello, in that short final beat, are like the hands of these lovers who finally touch, embrace, and grasp tightly, and that contact is perceived as pure love, laden with human truth. Thus it is that we have tried to return to the composer Gade - as though it were our hands which joined his - because music does not survive on paper alone; it requires a school, a constant intellectual effort to educate hand and voice, so as to keep it from "decomposing", decaying into an object which is merely an obsolete historical curiosity.

We have tried to make this recording a loving vehicle for the Trio of Niels W. Gade's artistic maturity; and while we could introduce it with his Novelletten of 1853, we had to decide whether to conclude with his only other work for this ensemble - the two movements in manuscript and without opus number, preserved in Copenhagen - or with the only Trio for piano written by Peter A. Heise, his friend and countryman. Ultimately our choice was based on our disbelief that the complete works of a composer must perforce include all of his notes, sketches, unfinished works, etc., where there is no evidence that he truly wanted to make them public.

Heise afforded us instead a unique Trio for piano written in Rome in 1863, and published in 1869 in Copenhagen, dedicated to his friend Giovanni Sgambati (1841-1914), noted pianist, conductor, and composer, who studied with Lizst.

Heise and Gadealso had the fact of having studied music in Leipzig in common. Gade continued his training in Germany, proving himself as Mendelssohn's understudy as the conductor at the Gewandhaus, and was later to return to his country and consolidate a definitively national style, also initiating non-Danish composers into a Scandinavian idiom. One example will serve: Edward Grieg.

Heise on the other hand was drawn to Italy and frequently stayed in Rome between 1860 and 1870, being of independent means. In Italy he produced a significant number of chamber compositions, influenced above all by his friendship with Sgambati and the cellist Ferdinando Forino. These two friends were perhaps at the root of the instrumental virtuosity and the sunny good humor evident in these works. Heise then became the preeminent composer of Danish songs, and the author of the opera "Drot og Marsk" ["The King and the Marshall"], which even today is among the most popular operas in Denmark. An encounter with Heise's music is always somehow joyous, captivating, full of life. In a Romanticism in which the dominant notion of "great music", is the tragic, the sentimental, and the sublime, Heise seems to stand out as the smiling composer, whose lightness is never pat or superficial. It is simply that, not possessing a tragic soul, he never tried to pretend that he did. For this reason, in 1869, he wrote a piano quintet "in a Joyous F major" offered "in reply" to the Brahms F minor quintet of 1865, which Heise had considered to be "affected by black melancholy". Thus his music without ever being fatuous or facile, rewards the listener with the peaceful and luminous gesture of his love for song and for life.

I firmly believe that it would be difficult to offer a meaningful introduction to Danish romantic music performed by Italian musicians in any other way. The interpretation of the three works to which we devoted ourselves, here has thus given us back a lesson in humanity, that truth of feeling to which we attempted to respond by giving a "body" to the sound of these two masters. There is much else to explore and to discover about them. Allow me to invite you to listen to these works with an ever-renewed imagination: if only they can create in you a new desire for music, then this is the reward for the musician who has lent them his voice.

Finally, a thought which accompanies our making of this recording: technology has responded to aesthetic criteria with products which seem to be perfect; and art can, alas, be replaced by the "beautiful", which satisfies the desire for perfection. To forget this fact leads to a serious confusion of values: the technologically "perfect" cannot replace the spiritually "perfect", because the former corresponds only to itself, that is, to the means by which it is created, and not to the complex of life and of thought. With this in mind we prepared ourselves to enter into the itinerary of these trios twice: first playing them on our instruments, and then recomposing, with the recorded fragments of our sound, a new poetic and musical thought in the final montage.

Claudio Ronco; Venice, august 1995.