The Wisdom of Apollo

«True beauty is SAPIENTIA»

«True beauty is SAPIENTIA»

Leone Ebreo

«All that which is beautiful is light»

Nietzsche

claudio ronco

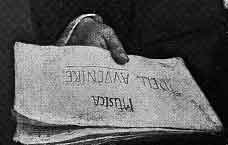

In a famous portrait by Francesco Hayez,

Gioacchino Rossini is shown no longer young, sprawled in a chair,

his gaze distant and inscrutable, his right hand on a half-open

score laid across his knees; on it we read in enormous letters

"MUSICA DELL'AVVENIRE",

(Music of the Future) the last

word underlined almost as though to shroud in uneasiness the

question: Who is the author of the music in that score? Was the

"future" in question the Zukunft of Wagner,

who had theorized it for the world in his 1848 book "The

Work of Art of the Future"? Or was it the sublimated essence

of Rossini's musical thought, projecred prophetically into a

possible or probable future, in which the out put of Italian

musicians could regain the authority it commanded in Corelli's

time? In fact, for almost two centuries the "language,"

the rhetoric, of musical expression had been constituted in the

sweet mellifluousness of the Italian tongue, bot now, in the

nineteenth century, the archetype was the sublime of the

visionary processes of German art. And Italy seemed to quail

before it, to fear the unknown, or rather that which seemed to

attract the Nordic mind.

From this springs the dissatisfaction

of modern interpreters who compare the works of the great German

classical composers with those of Paganini, Bellini or Donizetti.

Wherever vocality is the model of beauty and technique (even

violin technique), we rejoice in the richness and efficacy of

Italian music. But faced with the poetic itinerary and dramatic

greatness of northern compositions, we often end up concluding

that the Italians had little or no authentic sense of the tragic,

and that their music was only rhetoric (in the negative sense)

or hedonism, mere drawing-room entertainment. Only in the Opera

does everything still seem to find a balance and a persuasive

force, in a style born of an extraordinary naturalness in vocal

and instrumental technique.

This is the heart of the issue: the Italian

cellist or violinist will always be preferred for the beauty

of the way in which sound is drawn from the instrument, the so

called cavata, the "penetrative" quality of

that sound, its perfect fusion with the singers; others - Belgians,

Germans, the French - will be judged more brilliant in imitating

violin feats on the cello or in inventing new ones for the violin,

or more capable of mastering the contrapuntal complexities of

the chamber music of the great romantic composers. But no one

is remembered for melodiousness or for the beauty of their sound

as the Italians are. Thus even among violinists Paganini is as

much loved as he is hated by his contemporaries, as if he indeed

had to carry on his shoulders the weight of the entire Italian

baroque tradition, where the violin school - and the violinmaking

of the Cremona masters - were the matrix or the model upon which

all of musical Europe was based.

These were the arguments made repeatedly

for over half a century by all Italian composers and virtuosos,

in secking an explanation for the haughty disdain in which they

were often held, particularly by the Germans.

To better understand this reality we must

explore why the three Duetti concertanti for violin and

cello, composed in Varese in 1824 by Alessandro Rolla, could

very well have been conceived already in 1790, since little more

is discernible in them than the Corellian model applied to the

new style which Franz Joseph Haydn introduced with the famous

Quartets Op. 20, and to Bel canto melody. We must

also explore why the three Duetti concertanti by Nicolò

Paganini, composed at least ten years earlier, could be imagined

in any post-Classical period.

What in fact is missing in the music of

the Italian contemporaries of Beethoven? I find that we never

encounter the uneasiness of an oneiric imagery, or the desire

to plunge into the unknown regions of the mind. Mythology - beyond

that of Arcadia - does not seem a part of their musical language.

What is it then that generates "energy" in that language?

Perhaps the sensuality derived from a precise adherence to the

immediacy of the real, to nature as it is perceived by the body

taut with desire for erotic contact, harmonious contact, with

visible and tangible things. In this "triumph of the senses"

it would seem all the more possible to speak of an Italian musical

"eroticism". In fact the mind need not wander far to

gather the suggestions of this music: on the contrary, it must

remain attached to sound as to a body with which it must move,

must gather sudden sensations and immediate physical reactions

to musical effects. Thus the irrational is banished in a certain

sense insofar as it could induce casual reactions, difficult

to evoke by a programmatic rhetoric.

While the Germans were trying to represent

the "sublime" in the majestic phenomena of nature,

- those which inspire terror, or in the fantastic visions of

the unconscious, a region which was then yet to be explored -

for Paganini the expression of uneasiness can still be merely

a Capriccio: a whim. Here it is an ideally, perfectly

baroque Capriccio, where the heroic gesture is not that of the

great heroes of mythology, but only that of a man who, on his

artfully crafted wooden instrument, transcends the "weight"

of things and of the concrete. Inebriated with freedom he flings

himself into infinite space, secured by that "umbilical

cord" which holds him firmly to a fixed point in the universe

of sound: the tonality, the melodious framework, the technique

of his instrument.

In Rolla's duets, for example, the cello is used even in the

extreme high notes with brilliant technique, yet never departing

from the rationality of the form and nature of the instrument.

Rolla's inventions are thus simple and magnificent, polished

to create accompaniments of great polyphonic effect; and all

the richness of sound he can produce seems to be motivated solely

by the pleasure of contemplating itself. The themes in fact are

quite conventional, as though they need be nothing but mere pretexts

for the creation of the greatest beauty of sound and of ensemble.

Indeed everything is light, as if suspended in the network of

a structure which is itself solid and reassuring, so that every

emotion is expressed solely through virtuosity: from the fingers

and from the bow, and from the ideas which these know how to

soggest: emphasizing phrases with a variety of accents, attributing

various timbres to various melodies, and thus succeeding in transforming

musical suggestions ad infinitum thanks precisely to the

simplicity, or rather the Apollonean rationality, of the ideas

expounded and of their form.

Both in Rolla and in these Paganini pieces,

the care taken to "Italianize" their melodic phrase

is revealed in the "luminous" expansiveness of the

melody. The expression of melancholy always seems to be realized

by sweetening the phrase to the point of yielding a sense of

lack. The composition remains "energetic" as long as

it continues to maintain itself within the strict dialogue among

the two Concertante instruments, and every relaxation

of the phrase is the site at which attention is arrested by the

other: the one which before was accompaniment, now allowed with

loving complicity to dominate.

Thus this music seems to create an infinite game of love, that

of building an amorous relationship: giving, denying,

whispering, expanding. It all seems a search for vital impulses

that do not want to -and therefore cannot- oppose or contradict

nature. That is then why their formal schema is of necessity

simple, or "classical," and can only with difficulty

be imagined as rivolutionary or unsettling: the form must be

in some way reassuring, definite, immutable. The composition

thus becomes an exercise in civility, which explores a nature

conditioned by the equilibrium acquired by rational thonght;

it explores the best reactions to the stimuli of life, and the

performance, or its reception, becomes an exercise in the art

of living. The beginning and the ending of this music seem in

fact to be the most delicate elements in its performance: it

is there that we must create the conditions for a "pleasure"

which is not only an image of "beauty", but also the

immersion into an emotive experience strictly linked to the logic

of form and of harmony defined by classical academicism, by the

School, as a "second nature " It is thus that for a

musician such as Rolla, to play signifies an exercise of love,

just as it was in Renaissance neoplatonic schools; here, as in

those schools, one could believe that whoever loves beauty therefore

also loves -even if he does not know it- knowledge, wisdom; briefly:

the SAPIENTIA.

Perhaps it was Paganini himself who destabilized

all of this, with his musical philosophy which was a sublime

desire for freedom, possessed in the heroic gesture of extreme

virtuosity. In him all beauty is derived from lightness, from

the ineffable beauty of the "body" and nature of the

sound of his music. Everything is suspended toward the irrational,

and lives and maintains itself only by the reflection of the

natural, which it yet desires - or loves - to flee.

One thing seems certain: Paganini could

be all that he was, because his "umbilical cords" were

Rolla, Veracini, Corelli, or in the final analysis Apollo himself,

who dominates and balances the Dionysian revels. Therefore if

the Music of the Future is to communicate the desire for

a higher order, that order could be a repossession of Rhetoric,

which, imposing on us its limits, gives us the courage to explore

what is unknown to us.

N. Paganini (1782-1840): lithograph

(c1820) by Karl Begas.

Thus we set about performing these two

collections of Duetti concertanti on instruments suited

for playing Italian composers from the mid-eighteenth century,

recalling that Paganini's contemporaries described the strangeness

of his "bow of antique design" and of his choice of

strings. Above all we thought that the specific risk of playing

on instruments built 50 years before this music was written,

might be our response to the heroic gesture of our virtuoso composers.

We have performed their works intending to represent them as

a meeting between two musician friends, in the improvisation

of reading, in building a sense one fragment at a time, secking

out the surprise of the unexpected or of melodic phrases prolonged

beyond expectation, as though intended to lure us into an irresistible

current of musical ideas. We ended up convinced that these two

collections of Duetti - never published, intended apparently

only for a limited circulation among "music lovers",

who in that period might also have been virtuosos - are in fact

an important lesson for those who seek a deeper understanding

of Paganini's technique and style, which has so far been offered

in too rigid and aggressive a manner to be able to recover the

immense variety of sounds, the transparency and the lightness

which we would like to attribute to it.

We invite to follow the itinerary of our

collective improvisational instincts, which led us to explore

all the musical ideas realizable on period instruments, in the

firm conviction that they too can contribute to the Music

of the Future.

Claudio Ronco, Venice,

august 1995

back

to the top